The Hero of Jonestown: Congressman Leo Ryan

Updated: Jan. 20, 2024

Seven years ago, I ordered a unique government report from the Library of Congress online.

A nondescript reply arrived in my email inbox half an hour later. “Your requested item has arrived at the delivery location you specified,” a message said, referring to the main reading room of the Jefferson Library.

A ripple of relief stirred in me. Many times, I received the five-word reply all researchers dread — “Item not found on shelf.” After dinner I biked from my apartment on Capitol Hill and walked into the silent, palatial reading room.

A middle-aged, Black female clerk greeted me at the carousel and handed over a thick, manila book. “There you go,” she said smiling.

One night at the

Library of

Congress

The time was 7:35 p.m. on July 28, 2016. Hillary Clinton was scheduled to make her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in less than three hours. At that time and place, I was an oddball. I didn’t care. I had in my hands an object more valuable than a TV screen.

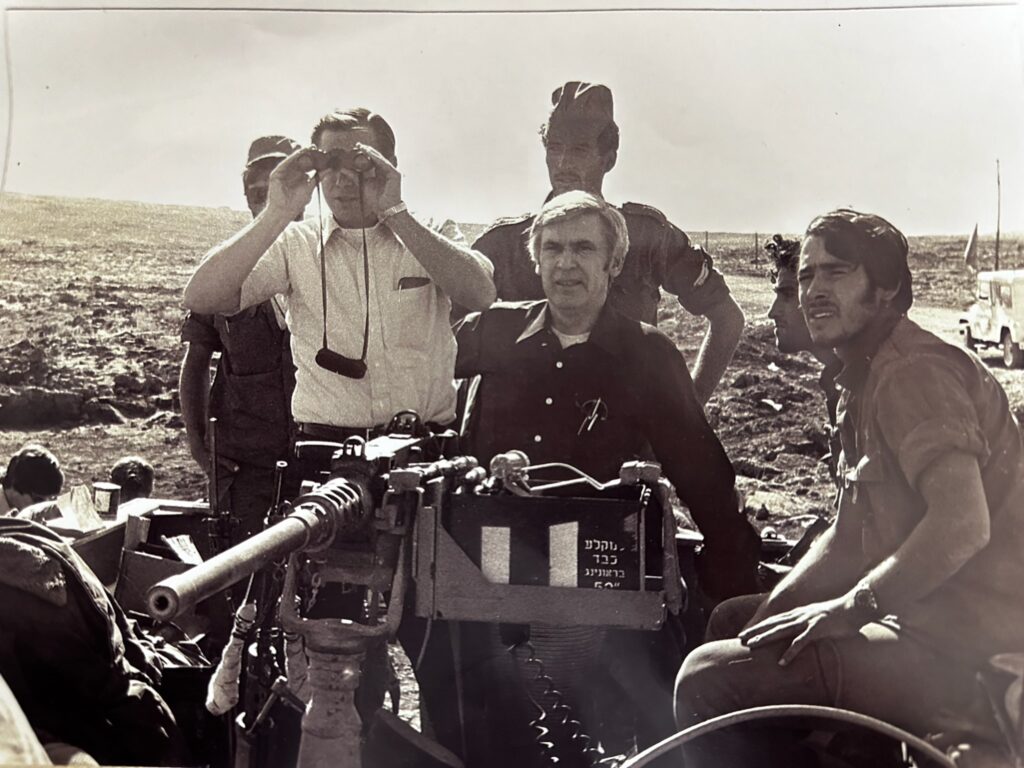

Representatives Ryan and Robert H. Steele, a Connecticut Republican, tour the Golan Heights battlefield in the fall of 1973 during the Yom Kippur War.

It was a government report into a congressman’s investigation of an infamous cult: “The Assassination of Representative Leo J. Ryan and the Jonestown, Guyana Tragedy: Report of a Staff Investigative Group to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives.” (Unlike the online version, the hardbound report had valuable footnotes and references).

Ryan had been my congressman (and state assemblyman) once.

My family lived in Burlingame, the heart of his district, California’s 11th, in the San Francisco Peninsula. I had been aware of his investigation of the Peoples Temple religious group. I gave Ryan no hometown discount, though…

Talk about a disaster. Man, oh man… He was murdered on a dusty runway strip in Port Kaituma, Guyana, with four others.

To make matters worse, Temple leader Jim Jones orchestrated the deaths of 913 more Americans in the remote South American country on November 18, 1978. Countless media had confirmed my low opinion. How could they not?

The Jonestown massacre’s images are so indelible as to be world famous. Riflemen leaped from a truck onto the airport strip to shoot at Ryan’s party before the camera went black. Piles of hundreds of corpses in red, yellow, and green clothes lay next to one another.

Later, I learned the story was… complex. By 1998, I had moved to Washington and covered Congress for two Bay Area papers. Lawmakers didn’t dismiss Ryan’s investigation. In 1983, they awarded him a Congressional Gold Medal posthumously for laying down his life for his constituents.

Ryan’s critics, though, kept up their attacks. Glory hound, loner, unwitting instigator of the massacre—the epithets suggested Ryan himself was to blame. Which side was right?

For reasons I will explain, by July 2016, I wanted an answer.

At the Jefferson library, I found a desk on the reading room’s eastern side. I started with the document’s 32-page summary. The first few pages described the genesis of Ryan’s investigation. I was surprised… This is weird. The congressman has a personal connection to this cult.

Reading the newspaper, Ryan learned an old friend and constituent, Sammy Houston, had suffered at the hands of Jones. Houston’s son, Bob, had been a Temple member. The day after Bob Houston announced his resignation, in October 1976, his mutilated corpse was found on a San Francisco railroad track.

Then Sammy Houston lost his two granddaughters. In August 1977, his former daughter-in-law took the girls to Jonestown and left them there. Houston, an Associated Press photographer, had contacted a San Francisco Examiner reporter, and the paper published a front-page story about him in November 1977.

Ryan read the story and “contacted the Houston’s and visited their home,” the report said. “Reinforced by the fact that a relative had been involved in an unusual church group, Mr. Ryan decided that the matter needed to be looked into.”

Image of Deborah Layton Blakey, former Peoples Temple secretary and later, defector and whistleblower, sometime in the 1970s.

A former Temple member too felt aggrieved. In June 1978, Debbie Blakey talked with reporter Marshall Kilduff from the San Francisco Chronicle. Blakey had escaped from Jonestown. As if that were not dramatic enough, also she wrote an affidavit in June 1978 warning the federal government that Jones conducted mass suicide drills.

I did a double-take. The woman predicted the whole thing?

The families of Temple members bolstered Blakey’s allegation. Far from being patient and adoring Temple supporters, they were critics.

“Further impetus came in letters he received from concerned relatives of People’s Temple members, some of whom were constituents, asking his assistance and alleging social security irregularities, human rights violations, and that their loved ones were being held in Jonestown against their will,” the report said, adding that Ryan met with the friends and family members in August 1978.

Ryan had not only a personal connection but also a professional obligation, according to the report. He was a member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. While the panel may draw a blank from 99 percent of the population, it played an important role in this case.

Diplomats and

Jim Jones

The committee oversees the State Department, and the State Department oversaw… Jonestown.

Yes, the State Department had primary oversight responsibility for Jim Jones’ cult compound. While we associate State with diplomacy, the agency has a paternal responsibility: to protect Americans living abroad from harm.

Yet the report suggested for the 1,000 Americans in Jonestown, Guyana State was a clueless inspector. Young teenage girls lived without their parents and Jones led his followers in rehearsals for mass death reportedly.

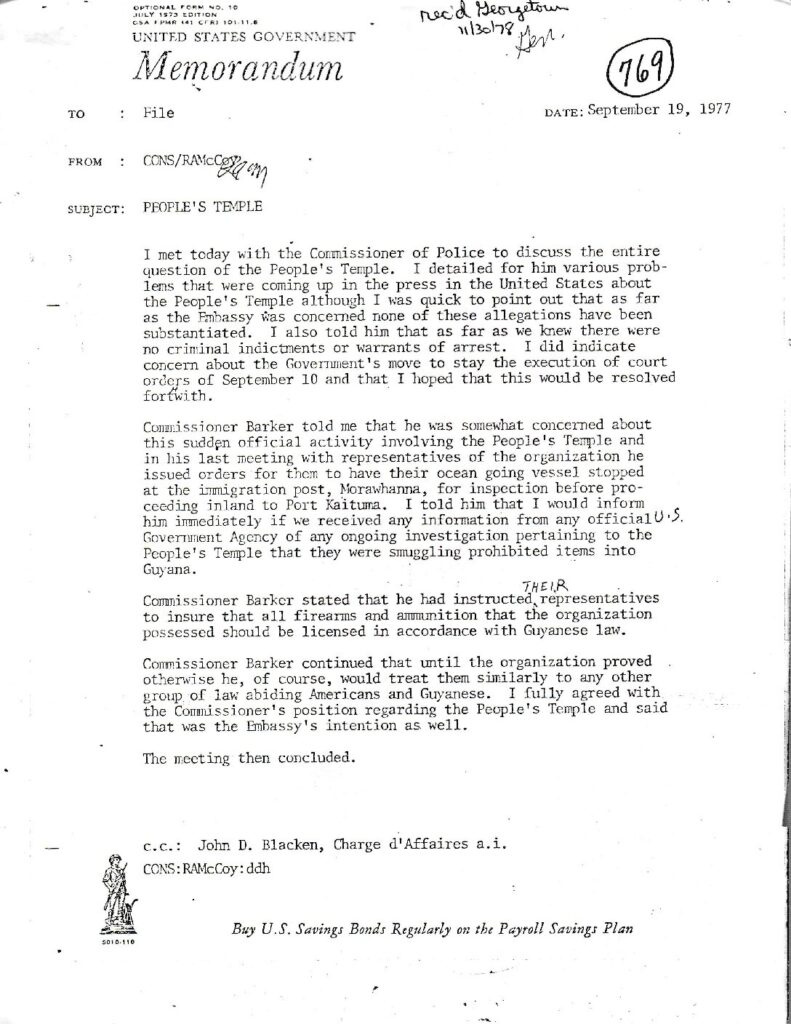

A memo from U.S. Consul Richard McCoy after the first of his three visits to Jonestown in late August 1977.

How did Ryan deal with the clueless inspector?

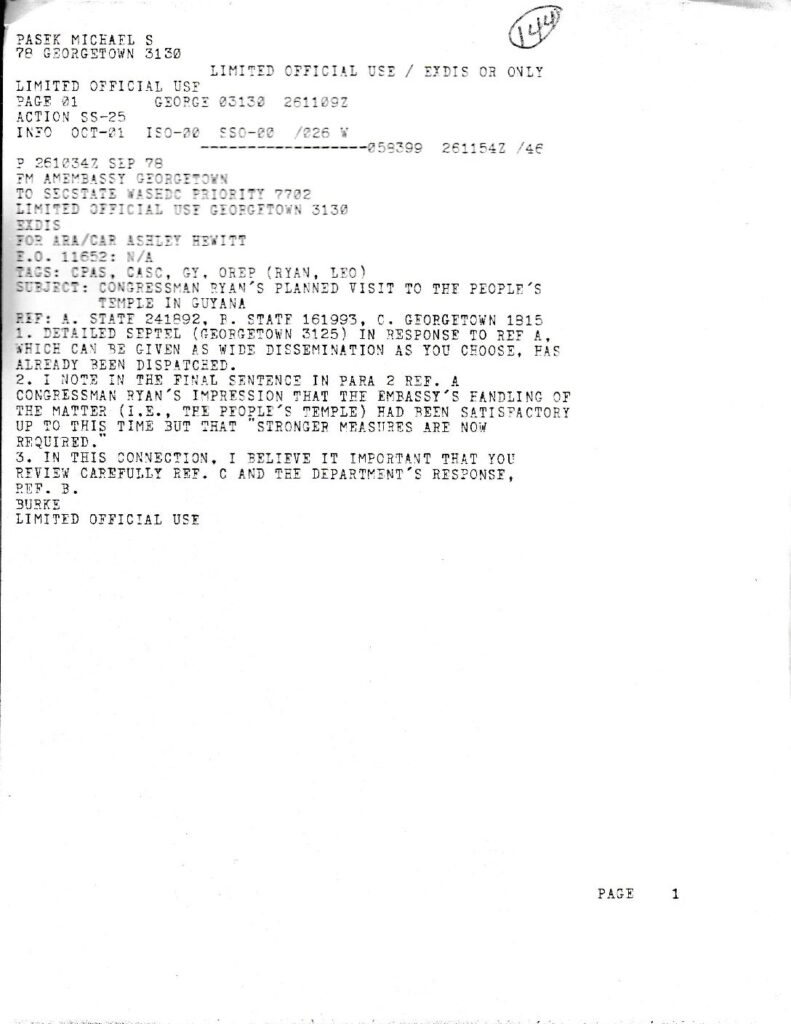

He questioned its sources. In August 1978, he hired a former aide to examine allegations the Temple had violated state or federal law. Yet he accepted State’s oversight authority. He collaborated with State on a visit to Guyana. On Sept. 15, 1978, Ryan met with Viron P. Vaky, assistant secretary of the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs.

“His staff met with State Dept. 4x—Oct. 2 & 25, Nov. 9 & 13,” I wrote in my notebook. On November 17 and 18, he investigated Jonestown with 17 others, including his aide Jackie Speier and Richard Dwyer, deputy chief of mission to the U.S. Embassy in Guyana. In later paragraphs, the report described Ryan’s arrival in Guyana’s capital, Georgetown, and, later, Jonestown.

Its finding surprised me. According to the report, Jones planned to kill everyone if Ryan left with defectors. “Large shipment of cyanide arrives the day before Ryan arrives,” I wrote in my notebook. “One survivor said Ryan’s plane ‘might fall from the sky.’” Dang. From the start, Ryan’s trip was doomed.

The congressman

and the cult

leader

Then the report made a strange turn. You would think that Jim Jones, as the possessor of a weapon of mass destruction, would act like Osama bin Laden. Instead, he acted like a minister weighed down by his dark secrets.

In vain he protested the congressman’s arrival in Jonestown. In vain he could not “delude Ryan as to the true condition of Jonestown,” according to the report. And despite the help of two lawyers who negotiated with Ryan, he didn’t stop his followers from leaving.

On November 18, Ryan left with 15 Temple members for the Port Kaituma airstrip for Georgetown. American Embassy officials professed shock. “Because of the unanticipated large number of defectors, an unexpected request was made to the Embassy in Georgetown at about noon Saturday for a second plane,” the report said.

By 9:20 p.m. at the Library of Congress, I scanned the rest of the summary and typed up my notes at home. Later, I considered the case against Ryan. Critics attacked his motives, but that was crazy talk. He operated more from empathy and a sense of duty than political expedience.

They attacked his operating style, but the report suggested this was misleading. Ryan may not have been a team player, but he wasn’t a loner either.

They attacked the outcome of his investigation, but the report indicated no one could have foreseen the Black Swan event that was the massacre. He had defeated Jones fair and square in the cult leader’s backyard.

Personal roots for an impersonal massacre

As I said, my project had personal roots. I was born in San Francisco in 1970. That was the year before Jones bought an old Jewish synagogue in the city’s Fillmore District, which would serve as his main headquarters until its mass exodus. My cousin Valerie O’Brien, a San Francisco public school teacher, taught nine or 10 Temple children who would die in Guyana. Jones’ abuse of his followers disturbed and fascinated me.

I viewed the Jonestown massacre as a horrible, mysterious event I had a personal if distant connection to.

Even Peoples Temple sympathizers—yes, they exist—acknowledge Jones abused people. His accomplices beat Temple member Neva Sly with a rubber hose, which prompted her to defect in 1976. They subjected two- or three dozen Temple members to a suicide loyalty test at the Temple in San Francisco in late 1975 or early 1976.

Jones raped and sexually harassed male and female Temple members alike. In Guyana, Jones acted more mercilessly. The man could be positively demonic. His accomplices drugged recalcitrant Temple members in an “Extended Care Unit.” They lowered disobedient children by their ankles into a dark well at night. They placed a snake on a woman who feared snakes. At least six times Jones ordered his community to carry out “White Nights” in which members pledged to carry out “revolutionary suicide” by taking poison and injecting children too, including infants.

Jim Jones, jailer

There was more. Jones may have kidnapped visitors to Jonestown. As my former CQ- Roll Call colleague Marcia Myers and I discovered, on June 2, 1978, 18-year-old Tina Lynn Grimm, engaged to be married, left the United States with her dad to visit her mother in Jonestown.

In August, her fiancée, Steven Loomis, contacted his congressman, John Burton, a California Democrat, for help to reach her. Grimm said she planned to return in two weeks for the couple’s wedding, Loomis wrote. “I have good reason to believe that she is being forced to stay against her will,” he wrote to Rep. Burton. “It has been two months now, and this is my last resort.”

Both Grimm and her father, and her mother, died on November 18.

San Francisco’s pols and the Rev. Jim Jones

Democratic politicians dismissed those potential injustices.

Instead, they saw a white minister in charge of a racially integrated church that claimed to do good works. Assemblyman Willie Brown said Jones was the second coming of Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi, Chairman Mao, and political activist Angela Davis.

Mayor George Moscone appointed Jones to the city’s Housing Authority, while in February 1978 San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk wrote a letter to President Carter in defense of Jones. As a result, the Moscone administration protected Reverend Jones.

The first time, they protected him from election fraud charges in 1975. Moscone had eked out a victory over City Supervisor John Barbagelata in the city’s mayoral election. With only 4,000 votes separating the two candidates, Barbagelata asked Moscone to investigate charges against the Temple.

Moscone’s response was shambolic. To examine the charges, he appointed none other than Tim Stoen, an assistant city attorney who moonlighted as the Temple’s attorney, despite Stoen’s complete lack of experience overseeing elections.

Yes, a Temple official oversaw an ostensible investigation into the Temple’s wrongdoing. Stoen found no wrongdoing.

The second time, the Moscone administration protected Jones from abuse charges. Former Temple members told federal and city investigators that Jones abused his followers and ordered the murders of defectors. City District Attorney Joseph Freitas responded to the allegations with the vim and vigor of an invalid. He told his investigators to slow walk any investigation.

After Jones fled to Guyana in July 1977, the investigators found him innocent of charges in San Francisco.

Inability to detect virtue signaling

By late 2014, I discovered a second reason for Jones’ elusiveness. He was an effective propagandist.

Not only did he gull ideologically sympathetic politicians, but he also gulled ordinary people.

I got a taste of Jones’ illusory tactics on a family visit to see my cousin Valerie at her house in San Francisco on Christmas Eve in 2014. As the family historian on my mom’s side, Valerie keeps family- and personal artifacts like the Vatican keeps Michelangelo’s artwork.

Jonestown had been in the news that August—federal officials said they discovered the remains of nine victims. She pulled out an old program from the Peoples Temple. It was a white cardboard and paper document with a colorful Temple logo on the front, a musty whiff, and pages that crinkled in your hands.

The Peoples Temple’s PR machine

To the uninitiated, the Peoples Temple had wide appeal. It had appeal to the religious. The program quoted the Book of Matthew 25-40, “For I say truly, whatever you did for one of the least brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

It appealed to the college-educated. The program contained blurbs from The Washington Post and San Francisco Chronicle endorsing the Temple’s work.

And it had appeal to Democrats and independents.

The program contained a black-and-white image of Reverend Jones walking alongside Mayor Moscone on the tarmac of San Francisco International Airport with vice-Presidential candidate Walter Mondale behind them, who, the program explained, had invited the two men to speak “in his airplane suite and then accompany him to his meeting downtown.”

Insufficient virtue of earlier investigators

I learned a third reason for Jones’ dodge. Like a serial predator in Hollywood, Division I college athletics, or the Catholic Church, Jones eluded investigators. He excelled at the dark arts—lying, cheating, stealing, bullying, abusing. By contrast, each investigator lacked one or more virtues—moral excellence such as justice, fortitude, temperament, and prudence.

I read Raven, an acclaimed history of the Peoples Temple. (The author, journalist Tim Reiterman, had survived the airstrip massacre at Port Kaituma). The book described a dozen investigators—12!—who let Jones off the hook. Reporter Lester Kinsolving wrote the Examiner’s investigative series in 1972.

While he displayed fortitude and justice, he did not show prudence. Kinsolving lost his equanimity in a public spat with Jones—he waded into a group of Temple members as they picketed the Examiner and made fun of their work. A year later, he decamped to Washington, D.C.

The reporters who saw through the Rev. Jim Jones

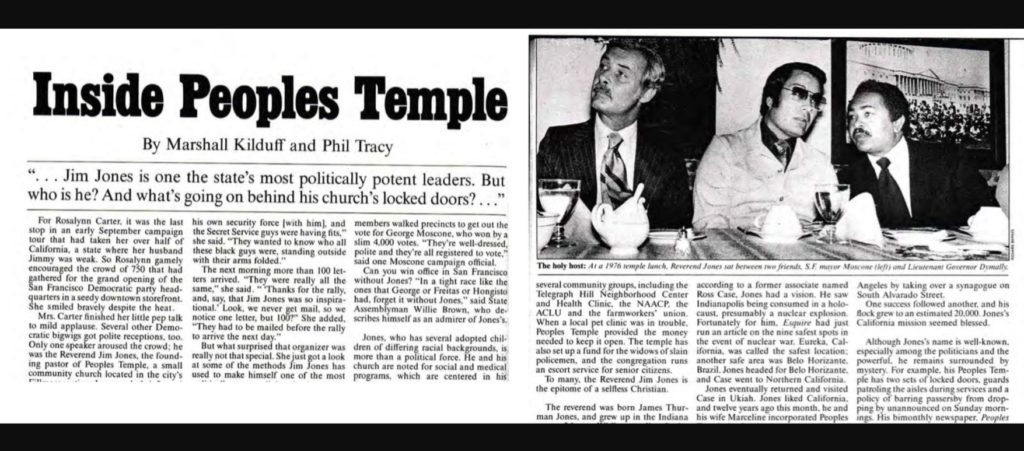

Reporter Marshall Kilduff was more prudent and temperate. In 1977, he teamed up with New West staff writer Phil Tracy on an expose of the Temple’s California operations; Mr. Tracy had interviewed Rev. Jones the year before. They interviewed 10 former Temple members who accused Jones of physical, sexual, and mental abuse on the record. Their expose was the newspaper equivalent of an atomic air burst.

Even before it hit the stands, the story exploded in the solar plexus of Jim Jones, who ordered his followers to flee to Jonestown after learning of its contents. Jones would have blocked Kilduff from stepping foot in his tropical preserve. While Kilduff showed prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, he was unfortunate.

The men who could not stop a bad man

Activist lawyer Jeffrey Haas was more committed. In September 1977, he drove into Jonestown to post a summons for Jones to appear in court in Georgetown, the capital, in a child custody dispute case. Haas lacked standing with the Guyanese government and did not return to Jonestown. He showed justice and prudence but a lack of fortitude.

U.S. Consul Richard McCoy of the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana, was even more committed. He went to Jonestown three times—August 1977, January 1978, and May 1978. He convinced Jones to pay for the expenses of a Jonestown refugee to return to the States.

While he showed prudence and temperance, his commitment to justice was insufficient. He did not challenge Jones’ authority. He did not bring in a team of investigators. And he could not verify the allegations. McCoy never returned to Jonestown.

American diplomats Richard Dwyer, Frank Tumminia, Doug Ellice, and T. Dennis Reece too drove into Jonestown at separate times. Yet they stuck to a familiar script. They stayed for four hours tops. And except for Tumminia, who registered his unease with Ambassador John Burke, they found nothing amiss. They showed temperance and prudence but a lack of fortitude and an insufficient commitment to justice.

Ukiah Daily Journal reporter Katherine Hunter and her husband, George, the paper’s editor, had a more evident commitment to Temple members. After they heard the abuse allegations, she went to Georgetown, Guyana, in May 1978. She encountered trouble right away; at the hotel where she stayed, three anonymous bomb threats and several minor fires broke out. Frightened and in ill health, she left for the States. The Hunters displayed justice but not fortitude.

National Enquirer freelance reporter Gordon Lindsay showed justice, too, but with more fortitude. He interviewed the whistleblower Blakey, flew to Guyana to interview U.S. and Guyanese officials, and even hired a pilot so they could fly over Jonestown. His subsequent report was a worthy follow-up to the New West expose. Yet the Enquirer lacked scruples. The publication sold the rights to Lindsay’s story to none other than Jim Jones.

Later, I learned a fifth American diplomat, U.S. Deputy Chief John D. Blacken, visited Jonestown. Black, Blacken heard allegations against Jones and recognized that the Guyanese government protected Jones. With Tumminia in February 1978, he shared a meal with Jones in Jonestown to discuss abuse allegations in February 1978. Yet he did not talk with ordinary Jonestown residents and found nothing amiss. He showed temperance but not fortitude and justice.

When diversity failed

The more I reflected on the investigators, the more I noticed a curious fact. They were a diverse bunch.

Kinsolving was a religious and conservative-leaning journalist.

Haas was a young and progressive lawyer.

Kilduff was a young, Stanford-educated city reporter from an affluent San Francisco family.

Ellice and Reece were in their twenties. Jim Hubert, the lead customs agent, was a seasoned federal investigator.

Lindsay was a British reporter.

Blacken was a middle-aged Black diplomat.

Hunter was a middle-aged female reporter.

These weren’t a bunch of old Christian white males. Many represented what we call today rising demographics and un-represented populations. None of that mattered. Despite their diversity, the investigators let Jones off the hook.

Who investigated him did not matter. Yet Congressman Ryan held him to account. How did he do it?

Virtue triumphant

The question was a challenge. The Jonestown scholarly literature treated Ryan as a minor or peripheral figure. The Congressional report presented Ryan’s point of view in a limited form. While I interviewed Jackie Speier, a Ryan aide who traveled with him to Jonestown (and represents most of his old district in Congress), I could not expect her to produce revelations long after the fact.

Then Dan and I got a break. On Wednesday, December 21, 2016, I called Fielding “Mac” McGehee, the principal researcher at the Jonestown Institute, an arm of the religious studies department at San Diego State University. Did he know any little-known or previously undisclosed research archives?

The National Archives has the records of the Congressional investigation of Jonestown, he said. Was he kidding me? I yelped or punched the air.

My place was less than two miles from the secrets of Ryan’s investigation. What’s more, I could find them in the same report of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs I had read at the Library of Congress in July.

I wrote a breathless email to Dan under the subject line “A likely research breakthrough.”

Mac said the material was released in 2008, has not been examined by researchers, reports on the motivations and actions of the principal characters, and is likely sitting on shelves in the National Archives in the DC archives,” I wrote at 6:42 p.m. on December 22. “Then I called and talked with Tom Eisinger, a senior archivist at the National Archives, who put the archive together. He confirmed no one has gone through the papers.

My days and nights at the National Archives

The word “archive” may conjure up an image of a vast and haphazard government warehouse like the one in the “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” In reality, the National Archives in Washington is a curated museum with original copies of the Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights, and Constitution. (Political leaders considered it so prestigious once the Warren Commission held its first meeting there, in December 1963).

On my first research foray, I took the elevator up to the second floor and walked into the Reading Room, a vast, airy space with pine desks, colorful banker lamps, and narrow windows overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue. After I ordered documents, a clerk pushed a gray-steel, squeaky, four-wheeled cart with a batch of records. The old-fashioned orderliness served me well. At the Archives I learned how to hold a cult leader accountable.

I started with the transcripts of the 62 people interviewed by the Congressional investigators in 1978 and 1979. The interviewees had an incentive to be honest. Their remarks and comments would be private for decades, which is why officials had slapped the type-written word CONFIDENTIAL at the top of each page.

Two things stood out; the attitudes to alleged victims and whistleblowers that impair or further the cause of justice.

Previous investigators saw Temple members as strange cultists. Consul McCoy described them as “highly suspicious” Americans living deep in the jungle, while Consul Ellice said he would not want to live in Jonestown with its outdoor plumbing and dirt roads but said Temple members had the right to do so.

How Rep. Leo Ryan saw through Jim Jones

Ryan’s attitude was different. It was paternal rather than professional. He perceived Temple members, especially the young, as vulnerable people with a special claim on the government’s attention rather than weirdos or crazy cultists.

Brian Bouquet, a 25-year-old constituent who moved to Jonestown, was a former classmate of his daughter Patricia’s rather than a selfish and misguided man who abandoned his doting mother. Judy and Patricia Houston, the teenage granddaughters of his friend and constituent, Sammy Houston, were the children of a late student, Robert Houston, Jr., rather than robots.

Most investigators discounted the whistle-blower, Debbie Blakey. Consuls McCoy and Ellice said they thought Blakey was sincere, but her charges struck them as outlandish, so they declined to look further. Ryan took Blakey seriously. At a Wells Fargo bank branch in San Francisco on September 1, he and aide Jackie Speier interviewed her for more than an hour.

From the meeting, Ryan reached two conclusions—the State Department had botched its oversight of Jonestown, and he should go there himself to ask questions and look around.

A State Department memo from September 1978 after Rep. Ryan met with personnel in D.C.

To help defectors

Earlier investigators appeared in Jonestown without a practical plan to rescue dissenters. Most State Department didn’t talk with Temple members; they exchanged pleasantries. Even Consul McCoy, a former Marine, didn’t convey strength to residents who might leave with him. He had nobody besides a colleague to challenge Jones’ authority, and only on his last visit, in May 1978.

In addition, investigators deferred to Jim Jones in Jonestown. The American consuls assumed he was legitimate. “What I tried to lay out to them from the very beginning was I was the American consul, I was as much their consul as anybody else because, after all, they were American citizens and they had the right to see me if they had a problem,” McCoy said. At most, the consuls asked Jones critical questions.

By contrast, Ryan challenged Jones’ authority.

Before entering Jonestown, Ryan warned Jones he might lose his religious tax exemption. No religious signs or services were in any pictures of the community, he noted. Ryan’s plan to rescue dissenters was more viable. It appealed to Temple members directly. “What if I were to go to Guyana, to Jonestown, and say, ‘If anyone wants to leave, I will stay here until anyone who wants to go can find a way out and I’ll provide some method of transportation?” he asked Blakey in his interview.

The word “if” was crucial. Temple members had to give consent to leave. Ted Patrick, an anti-cult leader in the seventies, at the request of family members, had rescued cult members whether they wanted to and had gotten in trouble with the law for it. After Temple members told Ryan they wished to leave, the congressman negotiated the release with Deputy Chief of Mission Richard Dwyer and Jones’ lawyers.

To be sure, the typical person on the street associates Ryan’s plan with failure. This is understandable but misguided.

Put yourself in Ryan’s shoes, and ask how you could have anticipated the black swan event of November 18. Jones’ abuse of his followers was well documented, while any killings he may have ordered were speculative.

Ryan could not control his investigation’s outcome. Yet he could control its process, and it was exemplary.

To put it in context, 10 organizations had investigated Jonestown:

— State Department

— Treasury Department

— FBI

— Guyanese government

— Los Angeles County district attorney’s office

— NBC News

— San Francisco Chronicle

— San Francisco Examiner

— Lawyer Jeffrey Haas

— CIA possibly.

None discovered Jones imprisoned people. Suddenly, Ryan showed up, stayed for a night, and sallied away with Temple members.

“A brave man”

The American Embassy’s Dwyer praised Ryan. In his interview with the House Foreign Affairs investigators in March 1979, at the end he was asked if he wished to add any relevant comments.

“I would hope the record would show clearly that Leo Ryan was a very brave man,” Dwyer said. “There was no doubt in my mind that in the time immediately preceding his death, his full intention and thoughts were the people he was going to help there.” Ryan’s investigation was a model of fortitude, temperance, prudence, and justice.

Think of the abuse scandals that have rocked innumerable American institutions—the Catholic Church, Boy Scouts, Hollywood, the U.S. Olympics, the Blackfeet Indian reservation in Montana, celebrity friends of Florida financier Jeffrey Epstein, and major colleges (Penn State, Michigan, Michigan State, Ohio State, USC). They span every ideology, social class, ethnic group, sector, and region of the country.

Generations of abused

Yet one thread unites them. In each case, investigators did not hold the predators to account until decades later, long after countless children, teens, and women were battered, molested, assaulted, or murdered.

You can draw many lessons to draw from Ryan’s investigation. The one I draw is as old as the Book of Ecclesiastes. Just as the swift don’t win the race always and the wise go hungry, heroes don’t control their glory. They can shape it. They can have a say. They can influence it. Yet they don’t have the final word.

Other people, too, have a say. That includes us. What’s our excuse? If Jonestown offers a lesson, it’s a sobering one. We may not recognize the goodness and virtue of heroes because of time, chance, and point of view.

-30–