Backward Ran the Dramatic Sentence

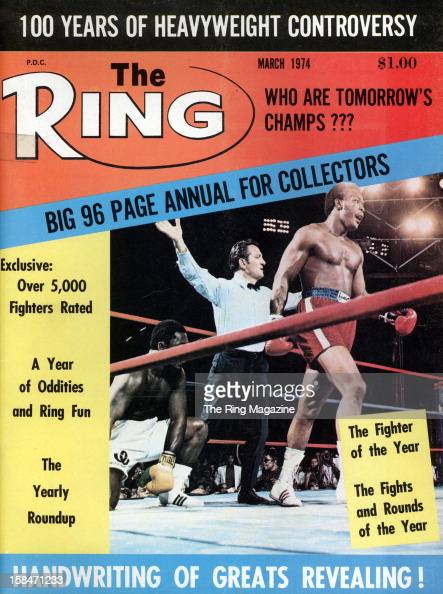

On January 22, 1973, Howard Cosell, ABC television’s announcer for the heavyweight-title boxing match between champion Joe Frazier and challenger George Foreman, uttered what may be the most famous lines in the sport’s history.

“Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” Cosell said after the 214-pound pugilist fell to the canvas in the first round of their bout in Kingston, Jamaica.

At the risk of sounding like a middle-school English teacher, I call your attention not only to the lines’ content but also their structure. They are inverted or backward sentences. Instead of following the typical subject-verb-object pattern, they scrambled this organization by putting the verbs ahead of the subject.

Many aphorisms of Yoda, the fictional, 900-year-old Jedi Master in the “Star Wars” series, are also examples of inverted sentences.

“Judge me by my size, do you?” he asks Luke Skywalker in “The Empire Strikes Back,” an example of a verb-object-subject sentence.

“Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter,” he said in the same film, an instance of an object-verb-subject-object sentence.

Inverted sentences can be found outside the precincts of popular culture. As Geraldine Woods, author of Twenty-Five Great Sentences: And How They Got That Way, notes, the poet Robert Frost used a backward sentence in the opening to “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

“Whose woods these are I think I know,” he wrote, whose inverted structure adds mystery to the identity of the woods’ owner. (Could it be God? … Some guy down the street? …)

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a (mesmerizing) backward sentence in the opening to his short story “The Tell Tale Heart:” “True!–nervous–very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am …Above all was the sense of hearing acute.”

Despite being well known, these sentences can nauseate readers if deployed too often. So often did Time magazine use them in the 1930s that New Yorker theater critic Wolcott Gibbs wrote a one-line parody: “Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind.”

Also, backward sentences can make no sense. “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!” is another famous sports line. Saying “The pennant the Giants win” or “The pennant win the Giants” would be idiotic.

Used sparingly and judiciously, however, inverted sentences help a writer achieve emphasis, a sign that a sentence is well written.

Stop and think about Mr. Cosell’s famous line.

If he had said “Frazier goes down!” it would be emphatic but pedestrian, the kind of line you would expect to hear from an announcer when a heavyweight champ crumples to the mat. By inverting a few words, Mr. Cosell uttered a line you could hear in casual conversation decades later by any American male 45 and older, or those in big cities at least.

Drama can be one effect of backward sentences. Doing the unexpected can be another, as the inverted sentences of Yoda and Mr. Frost’s show. Rarely do Americans talk or write like this, so their sentences heap attention on particular words.

Readers want drama and peculiarity. They don’t want sentences to drone on like Troy Aikman’s in his color commentary for Fox’s football games or Ben Stein’s “Bueller. Bueller. Bueller.” in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”

To be sure, inverted sentences are only one of 15 ways a sentence can achieve emphasis, as Thomas Kane, author of The Oxford Essential Guide to Writing, notes. And emphasis is only one of four signs a sentence is well-written, as he points out.

Yet by using inverted sentences selectively, alert and interested readers can be made and kept.

– 30 –

0 Comments