The Adult Amid the Hippies: Why You Should Read Joan Didion’s Early Essays

Revised January 4, 2022

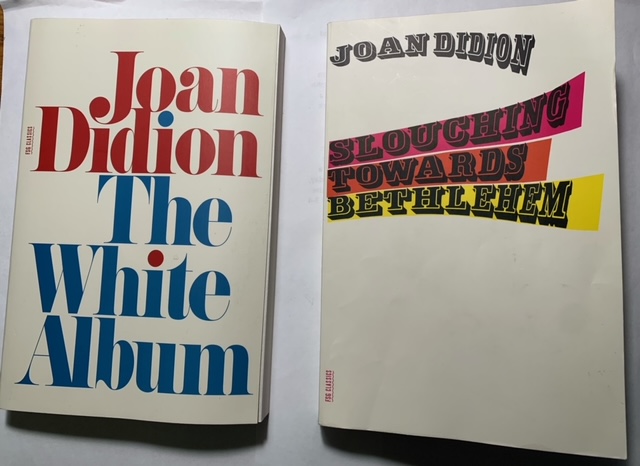

Early last fall, I read Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album, the first two collections of essays of writer Joan Didion. As my emails to my friend Dan and jottings inside the books attest, I was impressed by not only their literary style but also their content. Here was an American original.

Alas, on December 23, Ms. Didion died, at age 87. To anyone curious which of these justly celebrated writer’s books you should start reading, I recommend those two.

Ms. Didion explored a theme she returned to again in her long career. Adults should act like adults. When they don’t, bad consequences follow.

“Get off my lawn” wasn’t her message. It was something bigger: adults should be engaged with kids and set boundaries for them and if they don’t, whole neighborhoods and cities will crumble.

Ms. Didion said this in the late 1960s. That was a decade before books like Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism was published and religious and cultural conservatives emerged on the scene. Something was going on, to paraphrase Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man,” a famous song from the era, and Ms. Didion knew what it was.

Despite the country’s material prosperity, America was becoming poorer culturally and civically.

In particular, the emerging 1960s counterculture, the one with its flower children and hippies, wasn’t the unqualified good its advocated claimed. It had a dark side. Drug abuse was rife. Many kids grew up without parents effectively.

Ms. Didion was more than a Cassandra. She was a cultural and social diagnostician. She laid out reasons for the country’s emerging social atomization. Which, it seems fair to say, are relevant today as then.

Here’s what you should know about Joan Didion

Ms. Didion’s background is key to understanding her. For one thing, she was a fifth-generation Californian, which this brief, smooth jazz-inflected video below shows:

To an old-line Californian, this background suggests wealth and social respectability. The East Coast equivalent would be a person claiming old New England stock. He or she wants it known, as a member of Congress volunteered his old California roots to me while we were waiting in line at a Capitol Hill hardware store recently.

This background was important to Ms. Didion, too. In her essay “Many Mansions,” she mentioned that growing up she was acquaintances with the daughter of then California Governor Earl Warren, future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. (She told Ms. Didion, incidentally, she was “full of herself.”)

In addition, Ms. Didion, born in 1934, was a member of the Silent Generation. Again, this reference might be lost on most Americans, who are familiar with Baby Boomers and subsequent generations, but not those born between the mid-1920s and 1945.

Many Silent Generation members saw the world through the prism of original sin, the Judeo-Christian doctrine that humans are born selfish rather than perfectible. In a testament to the hold idea had on the American imagination, The Vital Center by Arthur Schlesinger, a well-known liberal historian, endorsed original sin as a guiding social principle.

Ms. Didion, too, said she had believed in Original Sin. In her essay “On the Morning After the Sixties,” she said she “belonged to a generation distrustful of political highs, the historical irrelevancy of growing up convinced that the heart of darkness lay not in some error in social organization but in man’s own blood.”

Also, by the late 1960s, Ms. Didion was not only an emerging woman of American letters but also a young mother.

She and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, adopted a daughter, Quintana Roo, in 1965. Can there be doubt that being a mom shaped Ms. Didion’s thinking? Consider the final horrifying scene in the essay “Slouching” about a young hippie family:

Sue Ann’s three-year-old Michael started a fire this morning before anyone was up, but Don got it out before much damage was done. Michael burned his arm, though, which is probably why Sue Ann was so jumpy when she happened to see him chewing on an electrical cord. ‘You’ll fry like rice,” she screamed. The only people around were Don and one of Sue Ann’s macrobiotic friends and somebody who was on his way to a commune in the Santa Lucias, and they didn’t notice Sue Ann screaming because they were in the kitchen trying to retrieve some very good Moroccan hash which had dropped down through a floorboard damaged in the fire.

Finally, Ms. Didion adopted the techniques of the New Journalism, the school that developed in the 1960s that sought to use the bag of tricks of fiction writers, in particular scenes and dialogue.

Ms. Didion’s New Journalism credentials can be overstated. In Slouching and The White Album, only a few essays rely on its techniques. She was an essayist and memoirist as much as a New Journalist. Even so, she wasn’t chained to her desk. She left the house, interviewed people, and witnessed scenes in person.

Put those four factors together—Ms. Didion’s regional, social, and intellectual roots, she was a recent mother, and her use of New Journalist techniques—and you have a writer and reporter who can portray the objective and subjective reality at the same time. She was no ideologue, but she was nobody’s fool, either.

What Joan Didion saw at the Revolution

As the counterculture emerged, Ms. Didion saw solid American values being inverted. Adolescence and egotism were prized, while adulthood was downgraded.

“I think now we were the last generation to identify with adults,” she wrote of her Berkeley education in “On the Morning After the Sixties.” “That most of us have found adulthood to be just as morally ambiguous as we expected falls perhaps in the categories of prophecies self-fulfilled.’

Ms. Didion said she found the women’s movement of the 1970s misguided and its most ardent voices juvenile. “To those of us who remain committed mainly to the exploration of moral distinctions and ambiguities, the feminist analysis may have seemed a particularly narrow and cracked determinism,” she wrote.

In a better-known essay in 1979, Ms. Didion excoriated Woody Allen’s films in the late 1970s for their jejune themes. “Self-absorption is general, as is self-doubt,” she wrote memorably.

This is not to suggest Ms. Didion was a proto-cultural warrior, a writer who sided with older Americans against the kids in the sixties. She could be as critical of her peers. In her diagnosis of the hippie movement, she blamed older Americans in part:

At some point between 1945 and 1967 we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing. Maybe we had stopped believing in the rules ourselves, maybe we were having a failure of nerve about the game. Maybe there were just too few people around to do the telling. These were children who grew up cut loose from the web of cousins and great-aunts and family doctors and lifelong neighbors who had traditionally suggested and enforced the society’s values.

Ms. Didion’s Tocquevillian and moralistic explanation for America’ s growing fragmentation may be simplistic.

As sociologist Robert Putnam showed, the fact that 90 percent of American households had a TV set in the late 1950s compared to 10 percent a decade earlier contributed to the decline of civil society.

The increase in recreational drug use and its availability in the 1960s may have been a cause as well as a symptom of social decay.

Nevertheless, Ms. Didion had grasped an important social insight. American culture and society were becoming juvenile and self-absorbed. Adults had power but did not use it responsibly. They retreated into their own worlds instead. Americans should feel grateful Ms. Didion, with uncommon charm and grace, warned us about this less-decried form of injustice.

What does everybody else think?

– 30 –

Nice essay, Mark! I feel like I can place her in the bigger picture much better than I could before reading it.

I’m more sympathetic than you to her worry that the blaming the counterculture might be too easy. (I certainly wish I didn’t know that instinct as well as I do, considering I managed to make my personal version of it both self-righteous and hypocritical). But I might spin it a different way than she does, though. Lately, I’ve been wondering if we all indeed make our individual moral choices, but history is not actually carried along by the aggregate of them? There seems to be some way that the river of history is carrying us along to some destination of its own choosing, and people’s individual choices are dictated by that flow? Often people’s choices that backfire seems to be coming from something acting upon them, where they are caught up in the “spirit of their times” rather than making a true free choice of their own. I have met people who knew they were choosing wrong, but only very rarely. More often, people somehow get tangled up in situations more akin to being caught up in a spider’s web of good intentions, bad luck, and an all-too-human failure to not remember how fast time and other people change. Maybe neither the “great man” theory of history, where a Jefferson or Churchill moves the fates, nor the moral blame game where Jeremiah’s castigate everyone for their laxity actually have much explanatory power. As with remembering the beam in our own eye instead of the mote in our neighbors, perhaps the adult Christian doesn’t get to see why history moves as it does, as much as just getting to take care of the casualties history sends out broken, reeling around us everywhere we look.

I agree history shapes us, but does it determine us? I don’t think so.

Read Joan Didion and the case against the Hippies, The Jules Evans Website to get a more balanced view of dear Joan.