A Diplomat Important Enough to Be Hated (Review #4)

(I corrected this post Jan. 18, 2023).

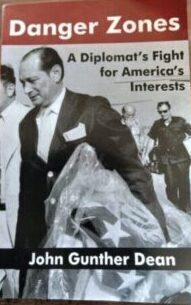

Danger Zones: A Diplomat’s Fight for America’s Interests. By John Gunther Dean. New Academia Publishing, 2009. 220 pages.

Score: 88 out of 100.

The career milestones of the late U.S. diplomat John Gunther Dean sound like a recruiting ad for the Foreign Service; well, almost. As an American ambassador, he helped foil a military coup in Laos in 1973, helped evacuate Americans in Cambodia before the government fell to the genocidal Khmer Rouge in 1975, survived an assassination attempt in Lebanon in 1980, and in India, raised questions about the mysterious fatal explosion of the plane that carried the president of neighboring Pakistan and the U.S. ambassador in 1988.

Mr. Dean’s action-packed memoir got me thinking. What if Americans got the leaders we wanted?

According to a Gallup poll in 2017, Americans said leaders of all stripes should be inspiring, compassionate, and a visionary. Roughly translated, we want leaders who won’t repeat the mistakes of the Iraq War and the financial crisis of 2008: they practice what they preach, care about people, and have a plan in which most people can get ahead.

We may no longer think of diplomats as leaders, but Mr. Dean’s life and career were marked by the three qualities we Americans say we want in our elite.

Inspirational: Born in Germany in 1926, he and his Jewish family fled Nazi Germany when he was 12 years old; he said the Nazis were so close to capturing his father that his father had to scramble down a flight of stairs in their apartment. His family bounced around Holland, England, and New York before settling on Kansas City, Missouri. (He changed his first name to John at the suggestion of a principal and his last name at the suggestion of his New York boyhood friends because the author of the popular memoir Be Not Proud was journalist John Gunther).

In 1973, Laos General Thao Mao organized a military brigade from nearby Thailand and seized the government radio station in Vientiane, the capital, as well as its airport and control tower. Ambassador Dean and his driver arrived on the tarmac, where Mr. Dean broke out a bullhorn to urge the sides to come together. When the bullhorn failed, he turned to Plan B:

From a distance, I could see that the government’s armed forces were not moving, either to support me or to support the rebels. Meanwhile, the propellers were turning on the small planes that the plotters planned to use for their raids. I had my diver move onto the tarmac and block the runway, thereby making it difficult for the planes to take off. My driver was scared and so was I. Stubbornly, perhaps because I had no other possible moves, I stayed in the car. General Ma…tried to fly off in the airplane had requisitioned, while trying to avoid hitting my car. As his plane took off, he veered to the right. Unable to lift his plane up, he crashed it on the side of the tarmac.

I took the bullhorn again. “Ok, guys, it’s over. Go back where you came from.

Mr. Dean notes none of the coup plotters or their enablers were held accountable. Still, they returned to Thailand, presumably with their proverbial tails between their legs, and the coup was over.

In 1980, as the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, Mr. Dean (and other State Department officials) condemned Israel for launching preemptive strikes against Palestinian targets in Lebanon. While he and his wife rode in the first car of a three-car caravan, they were attacked by assassins in a white limousine that shot 19 bullets and two missiles at their motorcade. Only the lead car was destroyed and nobody was hurt.

Compassionate: In 1972, as a military attaché in the northernmost part of South Vietnam, he helped rescue roughly two dozen U.S. troops after the North Vietnamese captured the territory via helicopter. In his last ride, enemy fire hit the helicopter’s gas line, forcing the vehicle to fall to the ground hard “like a sack of potatoes.” The pilot threw up a “Mayday” distress call, and another helicopter swooped in to rescue them.

Visionary: In the mid-1980s as the U.S. ambassador to India, Mr. Dean pushed the Reagan administration to strengthen ties to the Hindu nation rather than Pakistan, its Muslim neighbor. An emboldened could have helped empower Ahmad Shah Massoud as leader of Afghanistan. Instead, the Taliban took over the country, and assassinated Mr. Hekmatyar in September 2011.

Those achievements weren’t the result of happenstance. Mr. Dean was self-consciously an “activist diplomat.”

To say he was more concerned about talking with ordinary people and U.S. personnel than hosting fancy dinner parties for top officials might be a stretch; he described his dealings with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, India’s Indira and Rajiv Gandhi, and countless lesser-known world leaders in detail. Mr. Dean knew he needed to gauge the street as much as other embassies. As he noted,

The way I saw it, the only approach to the many festering problems and resentments in the country to which I was assigned was to talk to everyone in the country. The job of a diplomat is to see the whole country and everyone in it—get out of the Embassy, travel all over, try to understand people on their own terms, and report back to higher-ups in Washington and colleagues in the area about the possibilities and obstacles to peace.

Despite Mr. Dean’s admirable approach to his job and achievements, he is best remembered for a sobering event. He was the last American official to leave Cambodia before the Khmer Rouge seized control of the government in April 1975. A picture of a grim-faced Mr. Dean holding U.S. flags in a plastic case, the one that adorns the book’s cover, made the cover of Newsweek.

The Khmer Rouge, formed in 1966 from disgruntled Royal Army officers, slaughtered 1.5 million people in a country of 7 million. Mr. Dean urged the State Department to bring the warring parties to the bargaining table and warned diplomats if they did not act, he could not rule out the possibility of a “bloodbath.”

Drawing lessons from the life of a diplomat whose heyday was the 1970s and ‘80s is a dangerous exercise. The sample size is small indeed, and his era was less polarized than ours. Yet you can see patterns in his career.

Greater risk-taking will entail more injured

and dead leaders

Mr. Dean died in 2019 at the ripe age of 93. As he recounts in his memoir, easily he could have died decades earlier, in South Vietnam and Lebanon. A mere four years before his motorcade was attacked in Beirut, the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, Francis Meloy, was assassinated.

Recognition that leaders fall through no

fault of their own

Mr. Dean warned the State Department the Khmer Rouge could be the merciless bloodletters they turned out to be. State officials didn’t listen. They dismissed his warnings and didn’t support Mr. Dean in his attempt to craft a power-sharing agreement with them and other rival groups. The outcome could not have been worse, and none of this was Mr. Dean’s fault. He became ambassador in early 1974, only a year before the carnage ensued.

More negotiations will mean less ideological

posturing and fewer edicts

To be sure, diplomats have less ideologically charged jobs than presidents or members of Congress, but he believed diplomacy was preferable to war in nearly every case. This might sound benign, but its application is not.

While he was running for president in 2008, Barack Obama took flack for saying if elected he would meet with America’s enemies, including Iran. President Trump scuttled a plan to end the war in Afghanistan in 2019, which would have included a provision that the country not shelter terrorists, but the deal was scuttled because of an outcry on Twitter that he would meet with the Taliban.

Mr. Dean argues, convincingly in my view, that you don’t negotiate with friends; you negotiate with the enemy because you need rules to bind them to.

Danger Zones is a gem of a memoir that I would urge anyone interested in public affairs to read. Although the book could have benefited from more honesty about the toll his overseas career had on his family life and his mistakes, it contains valuable lessons for today. Among those is a realistic view of leadership in a populist age such as our own.

What did everybody else think?

-30-

I’m not convinced one would have a fair view of the actual history from just his recollections. Wouldn’t it be better to check with what other people said about those same incidents and also said about him?