A Guide to Nonfiction Writing: Forty-One Advanced Tips

(This is a repost from October 2023)

When I was twenty-four, I bought a copy of Conversations with Tom Wolfe, a book that contained a surprising truth: Even legends doubt their writing. “What am I doing?!” Mr. Wolfe fretted after quitting his newspaper job to write what became his first book.

He was not alone. “Why is this taking me so long?” Robert Caro has asked while writing books about powerful public figures. “I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself,” Joan Didion wrote of her work in the mid-to-late 1960s.

“Some very successful journalists are not very good writers”

Lesser lights struggle with clumsy prose. As former Wall Street Journal editor James B. Stewart wrote in Follow the Story, “Some very successful journalists are not very good writers.” He’s right. Scan the New York Times, Washington Post, or The Wall Street Journal. You will find sloppy, incoherent, and avoidably poor prose.

I wrote this guide partly out of frustration. Writing guides tend to invoke the usual suspects—Strunk & White, George Orwell, and William Zinsser. As wise as their advice was, it has become as stale as a month-old doughnut—e.g. Prefer the active to the passive or Write “say” or ‘says” rather than “explains” or “retorts.”

|

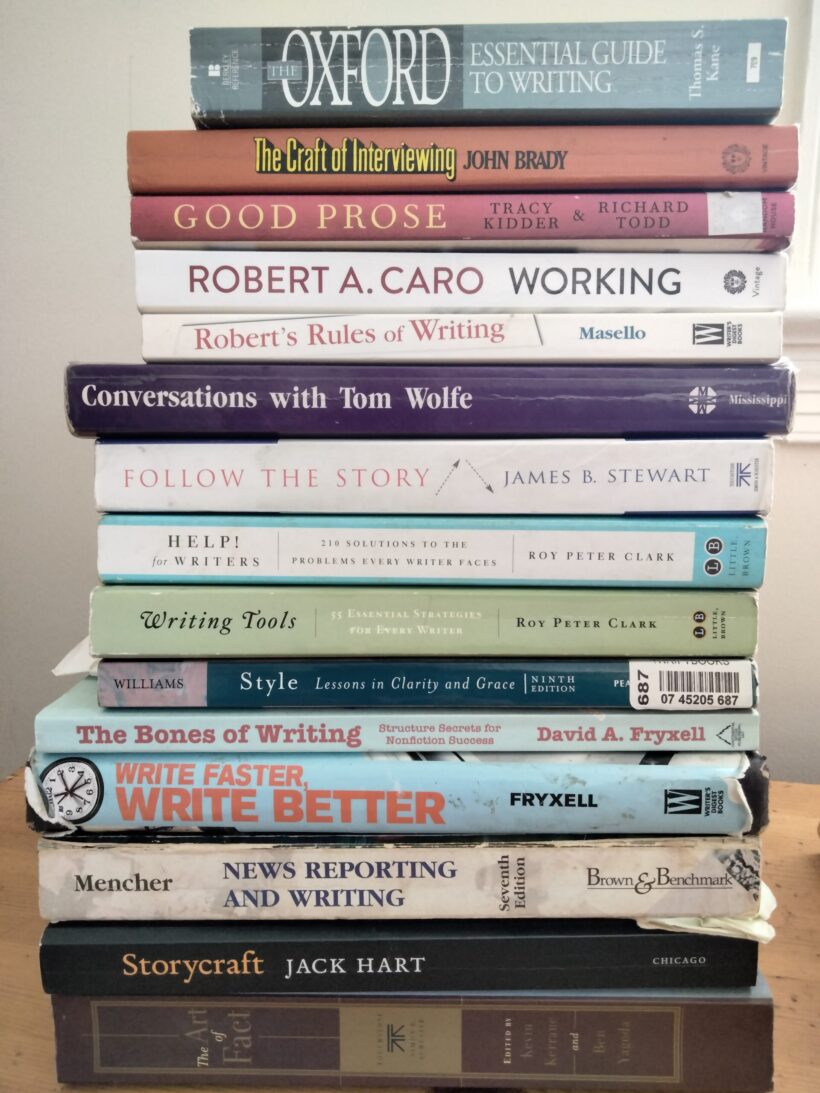

Since buying Conversations with Tom Wolfe in 1995, I have bought more than a dozen books on writing. Yet few writing guides invoked Joseph Williams’s Style, the Oxford Essential Guide to Writing, or John Brady’s The Craft of Interviewing. The absence strikes me as more than a “gap in the literature.” It strikes me as a deficiency akin to forgetting to add butter or olive oil to making scrambled eggs.

Follow these tips. They may not make you the second coming of Tom Wolfe or Joan Didion, but they will make you a more competent and professional writer. For the more philosophically minded, following them is also an exercise in the four cardinal virtues of prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice.

Professional journalists may find some tips to be unhelpful or saccharine. I hope everyone will find at least a few benefits. I broke the tips into seven categories:

I. Schedule (Tips #1-3)

II. Reporting (Tips #4-14)

III. Interviewing (Tips #15-23)

IV. Outlining (Tip #24)

V. Drafting (Tip #25)

VI. Writing and Revising (Tips #26-38)

VII. Fact-checking and editing (Tips #39-41)

I. SCHEDULE

Tip #1: Find when you work best— morning, afternoon, or night—and do your most intellectually difficult work then.

This lesson does not apply to daily journalists because of their unique pressure to make deadlines no matter the hour. For other non-fiction writers, I find this lesson invaluable. As writer and author Mason Currey concluded in his study of famous artists, “A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.”

A solid routine helped me write my book. I got up at 5:30 or 6 a.m. and worked from 7 a.m. to noon or 1 p.m. I was at my freshest and most alert. I felt this way for no more than five hours, so I had to seize the moment. Productivity, baby!

Some writers work best at night. See Mr. Currey’s Daily Rituals.

Bottom line: An exercise in temperance and prudence.

|

Tip #2: When writing a book, aim to draft 2,000 words a day.

Tom Wolfe said he followed this word quota while writing his books. I followed the quota not out of deference to Mr. Wolfe but out of necessity. Writing 1,000 words a day was insufficient for my goal of cranking out a book in a year.

Hitting my 2,000 words-a-day quota was a pain. I had to learn new tricks, including writing 400 words in an hour no matter my feelings.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence and fortitude.

Tip #3: For a break, walk around the block.

Working continuously is a temptation for office- and stay-at-home workers alike. You are required to crank out the story, the chapter, and the article! And sometimes you do. Yet I find this is seldom true.

A more prudential move is to get up out of your chair, leave the office or house, catch fresh air, and walk around the block. Ten minutes is sufficient. As a January 2023 article in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise noted, walking for five minutes every half hour not only counteracts the negative effects of sitting for prolonged periods but also lowers your blood pressure and wards off dementia.

Bottom line: An exercise in temperance.

|

II. REPORTING

Tip #4: Understand that reporting can be undignified.

In the short run, television anchors get the glory in the media. They are household names. They are treated as celebrities. Yet with a few exceptions, they stay in the studio rather than get out in the field to report.

This is not a coincidence.

Real reporting requires grunt work. Often, it’s the media’s equivalent of a police stakeout: The reporter waits … and…waits…and waits for something to happen. You’re on somebody else’s schedule. You must ask questions, which puts you at a status disadvantage. And to get the story, you may have to brave the elements and people.

To be sure, being a war correspondent has a romantic tinge. But that’s because Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell, and Ernie Pyle did it. Being in a war zone can be brutal and dehumanizing.

Bottom line: An exercise in fortitude.

Tip #5: Read 25 pages of a book every day.

Reading books is more than an important mental exercise. It also helps build up your background knowledge.

Reading books may not be sufficient or even necessary to write a good newspaper or magazine article. Reading them for writing books is, though. Books provide invaluable context for characters’ words and deeds.

I hesitate to recommend only 25 pages a day; I would prefer to advise reading 50 pages. Reading this number of pages is manageable. You need to read during meals, spare moments, after dark, and give up social media and television. With that in mind, 25 pages is a realistic goal. And you can read a book every two weeks at that clip: 175 pages in a week and 350 pages in two weeks.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence and fortitude.

Tip #6: Strive for objectivity, not false objectivity.

The ideal of objectivity has come under attack in recent decades. Since a certain public figure was carried down a golden elevator eight years ago, many media critics have written off the idea altogether.

This is a mistake. They are conflating objectivity with “both sides-ism,” the idea a reporter must present both sides of a conflict even if one side is morally abhorrent and the other just. You can argue this concern is overstated. Good reporters provide the necessary context for falsehoods, lies, etc.

In any event, a good journalist if not a nonfiction writer has the mindset of a referee, umpire, or medical doctor. She seeks the objective truth; she may not find it, but she seeks it. Objectivity is difficult to achieve, but the ideal is worth upholding like marriage and family.

Bottom line: An exercise in justice.

|

Tip #7: Avoid the conscious moral position.

In the late sixties and early seventies, Tom Wolfe advised writers to avoid taking the “conscious moral position.” While he did not define his terms, he indicated writers should report first and opine second. Don’t come to a story with your mind made up.

He’s right. Reporting and research give your story nuance and subtlety. To be sure, you can write stories so nuanced they lack a clear message. Yet without nuance and subtlety, your story becomes increasingly indistinguishable from propaganda or public relations.

Bottom line: An exercise in justice.

Tip #8: Call around.

Call five people a day on the phone. You may not reach them. They may hang up on you. Interviewing people on the phone is an essential skill for a reporter. You get outside your head. You tap into others’ expertise. And your story will be more authoritative.

Unquestionably, email is seductive. Type and send! Yet developing a relationship via email is difficult. What relationship would you have with your family if you sent them emails and didn’t call?

Bottom line: An exercise in justice and prudence.

Tip #9: Get out of the office or your home.

A confession: I struggle to follow this tip. In the moment, working from home is easy. No commute! No need to make or buy lunch or a snack! No need to wear fancy clothes or bundle up! And you can make a good argument for working from home a few days a week.

Yet in the long run, working from home invites distractions. Something in your house or apartment needs attention: laundry, the cat, the car, an errand. You feel harried rather than relaxed. The Economist looked at academic studies on working arrangements. The magazine found that while workers are happier working from home, they are more productive in the office.

I agree. Getting into the flesh-and-blood world makes you appreciate the “inexhaustible variety of life,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote. The people. The places. The flora and fauna. As I write this, in fact, I am in the main reading room at the Library of Congress.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence and fortitude.

|

Tip #10: Call archivists.

This tip is a variation on the advice to solicit spokespeople as sources. This feels counterintuitive. Haven’t researchers plowed through the archive already? Actually, no, they haven’t.

Ask New Yorker writer David Grann. He got the story that became Killers of the Flower Moon because he called archivists and asked if they knew of any untapped stories from the archives. Voila! An archivist replied that no one had written about the mysterious death of the Osage Indians in the 1920s.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #11: Scan or mine archives’ holdings.

You need inside information for this tip. No, not a Deep State actor but you need to find Someone in the Know—an official, scholar, or an autodidact.

I got my Jonestown stories this way. I had been exchanging emails and, yes, phone calls with Fielding “Mac” McGehee III, the head of the Alternative Considerations website and former Peoples Temple spokesman. I asked him if any archives contained files on Representative Leo Ryan’s assassination.

As a matter of fact, yes, there is, he said.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

|

Tip #12: Research until you hear the same story or stories repeated.

This tip is intuitive. When you come across the same information, rest assured you have done your homework. Does this mean you have a story? Not necessarily. Yet it means you can advance the story.

Bottom line: An exercise in fortitude.

Tip #13: Imitate your characters.

For my Jonestown book project, I went to a gun range to feel what it was like to be a perpetrator and a victim of an ambush.

My main character, Congressman Leo Ryan, and his party came under attack from Peoples Temple assassins at a remote airport strip. While two victims wrote books about the event, their accounts didn’t answer my questions. What does a bolt-action Remington Model 700 rifle feel like and what sound does a .308 cartridge make? Without those answers, I feared readers would be in the dark.

A version of this reporting method is central to acclaimed historian Robert Caro.

He follows an interview subject to the same place where a significant event to that person or a friend or family member occurred. Mr. Caro said he interviewed one of Lyndon Johnson’s brothers at their old family dinner table. Mr. Caro wasn’t being nostalgic. He thought being at the spot where the Johnson family ate meals might trigger memories.

And it did. Lyndon Johnson’s brother recalled the many fights his father and brother had at the dinner table. More famously, for his first biography of LBJ Mr. Caro moved his family from New York to the Texas Hill Country region.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

Tip #14: Turn every page.

This tip is also from Robert Caro. In Working, he recounted the roots of his investigative work.

He was a reporter for Newsday and while working one Saturday afternoon all alone in the newsroom, he received a call from a federal official who tipped him off to a story. The Federal Aviation Agency wanted to convert a large military airfield for civilian use instead of as an extension for a university; the federal officials did this not out of civic pride but because business interests wanted a convenient airport.

Mr. Caro was permitted to view the files at length. He found a pattern of businesses pressuring the feds to convert the military airfield for their personal convenience.

When Mr. Caro’s boss found out, he was ecstatic and gave him the advice he recalled half a century later. “Just remember. Turn every page. Never assume anything. Turn every goddamned page.”

I have mined university, presidential, and the National Archives. I agree with Mr. Caro: Turn every page!

Bottom line: An exercise in fortitude.

III. INTERVIEWING

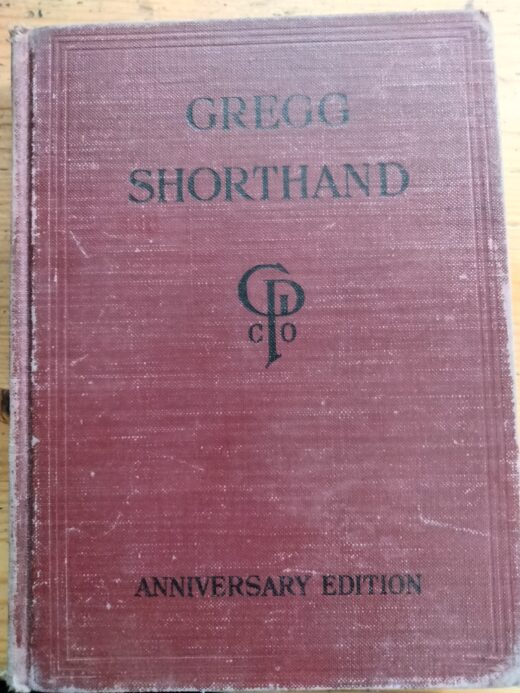

Tip #15: Learn shorthand.

I admit that learning to write in shorthand is a pain. You need to know the symbols for all 26 letters in the alphabet and apply them to countless word combinations. Yet the long-run benefits are worth the effort. Among other things, writing in shorthand saves time. You take notes faster and more efficiently and feel more confident during interviews.

The two main shorthand methods are Gregg and Pittman. I learned Gregg, though not nearly as well as Dennis Hollier, who says he can transcribe 225 words in a minute. I use Gregg to write common and familiar words— “the,” “good,” “from,” “advance,” “business.”

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence and fortitude.

|

Tip #16: For every minute of conversation, prepare for ten minutes.

The ten-to-one rule is not ironclad; five-to-one or eight-to-one may work equally as well. Yet the principle still stands. To enter the interview subject’s subjectivity, a writer should have read or talked with an authority.

For my Atlantic profile of Dinesh D’Souza, I read part of his book Illiberal Education, heard from two friends who had attended one of his lectures or worked with him, and followed his career in the news. I did not bone up for my ten-minute interview with Mr. D’Souza the night before, but I had read or talked with people about him for more than 100 minutes.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #17: Show up to an interview without a pen and pad.

Making the interview subject treat you like a normal person rather than a reporter is an art.

Unless they are professionals, they will proceed cautiously if at all. Little gets their back up quicker than a pen and pad. They go into spin-control mode, and your odds of a productive interview diminish. Hence the need to disarm them.

One reporter explained the idea to me this way: Ask the interview subjects about their family lives, talk for a few minutes, and whip out the pen and pad when the person feels comfortable.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #18: Avoid using a tape recorder for interviews.

The exception to this rule is a “scrum” when many other reporters congregate around an interview subject such as an elected official on Capitol Hill. Often, the tape recorder saves the reporter, especially when the interview subject speaks softly or outside noises are deafening.

In other cases, using a tape recorder hurts more than it helps. It makes the interview subject feel self-conscious. As Gay Talese said, the interviewer gets the talk-show version of the subject rather than the person unscripted. Scripted is bad! You want the person to feel relaxed and comfortable.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #19: Expect a public figure to make false statements.

I know, newsflash: politicians say untruthful things! …

Yet the message bears repeating. Public figures misstate facts, utter half-truths, and lie. A reporter must be on guard with even sympathetic interview subjects and sources that their words may depart from objective reality.

Bottom line: An exercise in justice.

Tip #20: Start by showing the interview subject you know your stuff.

Please see my post on how to interview a senator or congressman. With certain exceptions, an interviewer aims to gain his or her subject’s confidence. The most reliable method is to show you understand something about his or her subjectivity or world. You’re not Joe Blow reporter conducting an uninformed interview. You did your homework.

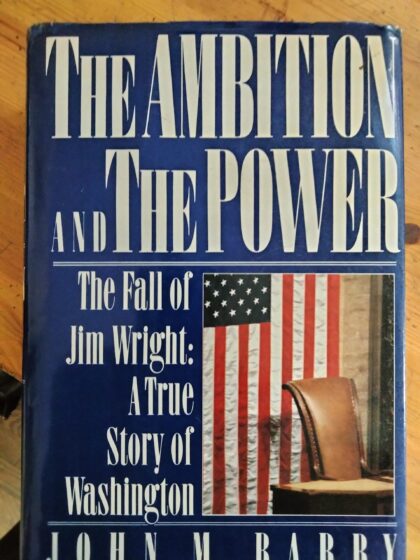

Take my profile of Representative Patrick T. McHenry, a North Carolina Republican.

He was candid with me partly because I asked him detailed questions, especially about his favorite books, especially John Barry’s The Ambition and the Power. “All the other reporters ask me about which movie I saw recently,” he said, adding he has little to add because he watches films his children watch. “You’re the only one who asks me about the books I’ve read.” I had done my homework; he cited numerous books that revealed his political evolution; and the reader was the beneficiary.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

Tip #21: Let the subject talk.

Letting the interview subject talk is fundamental. Not only is it polite, but it also brings comfort to the person. You can interject, especially if he or she lies or makes false or questionable statements.

Yet don’t interrupt and signal approval or disapproval. This is not a debate. It’s an interview. You’re on the subject’s terms, not yours.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #22: Assume you asked too few questions.

Interviewing can be an emotional and spiritual challenge. On the one hand, as an interviewer, you feel good when a subject agrees to cooperate. You got the interview! She’s a big shot! On the other hand, you are tempted to ask too few questions. You fail to ask who, what, where, when, why, and how.

To address this problem, the writer John Brady had a three-word phrase: “Dumb is smart.” If you don’t grasp an idea, say “I don’t understand.” This makes the interview subject feel heard and prevents the embarrassment of being unable to answer your boss’ questions.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence, fortitude, and temperance.

Tip #23: After an interview, type up your notes.

Your handwriting may be impeccable. Mine is not, and I venture most readers’ is not either. My symbols and letters are all but indecipherable after a few hours. Yet transcribing them within 24 hours enables me to recall the events from short-term memory. Here is an example:

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

IV. OUTLINING

Tip #24: Describe your thesis in seven words or less.

David Fryxell advised this in his appropriately titled Write Faster, Write Better. He argued that the fewer words you use to describe the thesis of your article or book, the better. Your message is distilled into something memorable.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

V. DRAFTING

Tip #25: To avoid getting stuck on first drafts, use a manual typewriter.

Some writers get stuck on their first drafts. The draft becomes an agony of stopping and starting. I know the feeling! While writers recommend many strategies to plow through a first draft, I appreciate the virtues of manual typewriters.

If nothing else, they force you to get your thoughts on the page. This is the single most effective strategy I know.

This tip won’t be for everybody.

Buying a good manual typewriter can set you back $100 and require hours of research. Many writers fly through their first drafts. There are other tricks to writing a first draft quickly: forcing yourself not to look back at your copy or setting an hourly word limit and following it.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

Tip #26: Understate grave events; overstate trivial ones.

This tip is deceptively simple.

When describing people suffering grievously or dying, a writer should adopt an understated tone. “It was in Burma, a sodden morning of the rains,” Orwell wrote in “A Hanging.” “A sickly light, like yellow tinfoil, was slanting into the high walls in the jail yard.”

When describing people doing trivial activities, a writer has room to be creative. “(E)ven at their worst, the Padres’ uniforms could not approach the pupil-gouging horror of the Houston Astros’, circa 1975-1979,” Dan Epstein wrote in Big Hair, Plastic Grass, his outstanding chronicle of 1970s Major League Baseball. “Something about them…smacked of chain motel bedspread or 747 jumbo-jet upholstery.”

You could argue that the “Florida Man” genre subverts this lesson. A bone-headed Floridian gets drunk, falls into a swamp, and is eaten by a gator! That argument can’t be dismissed. Humorists revel in dark humor; witness Evelyn Waugh. Yet dark humor is more of an exception than a rule.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence and temperance.

V. WRITING

Tip #27: Motivate your readers to read right away.

Writing about a topic or what you know is every writer’s mistress. You turn to it to feel satisfied and strong.

Yet she is a short-term fix. She hurts writers in the long run. She keeps them away from their true loves—their audience.

What’s the solution? Try to solve your audience’s problem, not just yours or a few people you know. Motivate your readers and they will reward you with their time. This is a tall task; getting out of our heads is difficult.

The solution is to open your article, chapter, or memo with a statement that appeals to a wide audience; this is called “shared context.”

In Style, the late University of Chicago’s Joseph Williams cites the example of writing about binge drinking by opening not with the topic but with the broader subject of alcohol. “Alcohol has been part of college life for generations …” Many readers can relate. Then, he qualifies the statement by introducing the topic of binge drinking. “Alcohol has long been part of college, but a new form of drinking called ‘binge drinking’ is increasingly popular.”

Think of the advice as “reaching readers where they are.” You recognize they know something, then show them something they might not.

Mr. Williams acknowledges some articles or books should open with an anecdote, a surprising fact, or a memorable quote rather than the shared context-problem-solution sequence. Yet the writer needs to bow to the audience with a shared context at some point.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #28: Motivate your readers not just globally but also locally.

This tip is a variation of the above. Not only should writers motivate their readers for their whole article or book, but also for each section and sub-section. Readers want to see the point of a passage. Without motivation, they will move on.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #29: Keep subject-verb-object together.

This tip is more akin to a rule: Don’t break up the subject-verb-object sequence. She hit him. He carried her. The tree fell onto the ground. Keeping the sequence together ensures clarity. Readers can follow the logic because the sequence is tight.

Some observers may object that newspapers violate the sequence routinely—e.g. “President Biden, who appeared on television Sunday, renewed his vow …” Yet reporters do this for lack of time more than anything else; they are writing for accuracy more than style or crystal-clear clarity.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #30: Avoid the -ings.

In colloquial speech, people use gerunds and present participles promiscuously. “We are going to church.” “She was riding her bicycle.” “He is good at painting.”

This is understandable to a degree.

To say “I watch birds” rather than “I am watching birds” is awkward. Yet the exception has become the rule.

Instead of “She was riding her bicycle,” say “She rode her bicycle.” You save a word and gain clarity.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #31: Make your lead clear.

You can lose a reader with a bad lead. Gaining a reader is a trickier proposition.

Try to replicate a memorable lead such as “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times…” It’s a tall task.

To keep a reader, strive for the clarity of water in a mountain lake. A clear lead is on point if nothing else.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

|

Tip #32: Put familiar information first and unfamiliar information last.

This is my favorite recent tip: Put information familiar to your reader at the beginning or the left part of your sentence and less familiar information toward the end or the right-hand side. Follow the sequence!

Why? Clarity, for one: The sentence is easier to read, and makes fewer demands on your reader. Compare these two sentences:

The Lakers beat the Warriors in game four of their playoff series on the strength of Lonnie Walker IV’s fifteen points in the fourth quarter.

Lonnie Walker IV’s fifteen points in the fourth quarter powered the Lakers to victory over the Warriors.

Which sentence is easier to read? Except for Lakers diehard fans, the first sentence is easier to read because Mr. Walker was a little-known role player until his breakout performance in Game 4 of the NBA Playoffs this spring. More readers know who the Lakers and Warriors are.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #33: Use the five senses.

Sense, smell, touch, taste, and hear—remember those? They are the five senses, the quintet through which we apprehend the outside world. As the description suggests, they are fundamental rather than optional or recommended. Using them in your writing makes your prose immersive. A reader can experience the scene or description as you describe it.

|

Tip #34: Write about things you can drop on your foot.

This tip elaborates on tip number 35. Borrow a page from Ernest Hemingway and write in terms of objects rather than ideas. Take, for example, his description of an execution of six ministers. Instead of saying the deaths were grisly or horrific, “Papa” wrote about the executions in terms of things you can drop on your foot. “There were wet dead leaves in the paving of the courtyard,” he wrote. “It rained hard.” The images emphasize the scene’s bleakness.

Hemingway’s vivid prose is no accident. According to writer and writing instructor John G. Maguire, good writing uses concrete nouns rather than abstract ones. The writer’s job is not to pull back or abstract from reality but to describe it as is.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #35: Go up and down the ladder of abstraction.

Using concrete nouns gets a writer 90 percent of the way toward clarity. The other ten percent comes from using abstract words appropriately.

Does this not violate tip number 36? Not really; I square the circle by urging readers to climb up and down the “ladder of abstraction” —the term San Francisco State University linguist (and one-term U.S. Senator from California) S.I. Hayakawa used to describe the spectrum along which concrete and abstract language lay.

A concrete word such as “foot” sits at the bottom of the ladder. An abstract one such as “clarity” at the top. A bureaucratic word such as “facility” or a phrase such as “standardized processes” sits in the middle rung. Few enjoy reading bureaucratic piffle. Yet many people like to read words that sit at the top rung occasionally. America is the land and home of the free and the brave, after all.

A good example of a passage that cites words from the bottom and top of the ladder of abstraction is George Orwell’s 1936 essay “Shooting An Elephant.” In the climactic passage, Mr. Orwell invokes concrete words such as “rifle” and “puppet” alongside abstract ones such as “dominion,” “freedom,” and “futility.”

(A)s I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man’s dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd – seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality, I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #36: Avoid nominalizations.

A nominalization is a verb or an adverb used as a noun: discover becomes discovery, recognizes becomes recognition, and resist becomes resistance. In most writers’ hands, nominalizations are a mistake. They are abstract and wordy, straining readers’ minds. No one has a mental image of a discovery or a recognition. See tip #35 above.

At times, nominalizations are needed for the sake of brevity. Columbus’ discovery of America transformed the world. Yet they are used far too commonly. Many writers don’t say, “Progressive activists resisted President Trump’s policies.” Instead, they write, “The resistance of progressive activists was aimed at President Trump’s policies.”

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

Tip #37: Killer filler words.

Strunk and White were right: Filler words are leeches that suck your prose of its blood. They include “very,” “seriously,” “little,” “that,” “perhaps,” “even,” “maybe,” “sort of,” “in,” “on,” and “for.” These words are hurdles the reader must jump to reach your sentence or passage’s finish line. If you erect them in your drafts, knock them down in your revisions.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.

|

Tip #38: To make your writing descriptive, use cumulative sentences.

Do you have this problem? Too often, your sentence patterns are familiar and dry. They consist of simple, compound, and complex sentences with an occasional repeated phrase thrown in.

Alas, I do. To get out of the rut, I use a cumulative sentence, which tacks together dependent clauses to such an extent they outweigh the independent clause.

Take, for example, the opening of my sample chapter in my proposed book on Jonestown: “Jonestown was carved amid a rainforest in the North West of Guyana, one of the most remote places on earth, with fewer than one person per square kilometer, a population density greater than Greenland but less than the Western Sahara and Mongolia.”

The sentence is both emphatic because the three dependent clauses emphasize Jonestown’s remoteness, and varied compared to later simple- and compound sentences.

VII. Fact-checking and editing

Tip #39: When in doubt, cut it out.

This is a hoary newspaper adage. If you doubt a fact is true in your story, remove it.

Nothing is worse than an error. It requires editors to issue corrections, which wastes their time and effort. I have drawn a paycheck from seven newspapers or magazines. To a publication, each one has treated errors seriously.

Tip #40: Assume your final draft has errors, so print out a draft and read it aloud.

This tip is easy to advise and hard to practice. In our digital age, who likes to admit he might be wrong? Who likes to print out a draft and look for errors and typos?

Not me! Until recently, I struggled to apply this tip consistently. Why waste paper? Didn’t I work hard on the story already? Avoid the easy route. Recognize that producing good work is difficult. Push yourself.

If the above sounds like disposable advice, try submitting your copy to good editors. They will hammer you for sloppy writing, for wasting their time, for being unprofessional. They will be right!

You will be amazed by the errors and typos you find after printing out your copy. I caught two- or three regularly while at CQ Roll Call. One more thing: Read your drafts aloud. You hear your words. And yes, spellcheck makes mistakes.

Bottom line: An exercise in fortitude and prudence.

Tip #41: Edit for style.

It’s one thing to edit to correct mistakes such as typos and errors. It’s another to edit for style as well. Hunt for -ings. Make sure familiar information comes first and less familiar information comes later. Look to add concrete nouns and strong verbs. Editing systematically doesn’t guarantee words that sparkle on the page, but it helps prevent bad prose.

Bottom line: An exercise in prudence.