Head Trip: A Page Turner about a False Prophet (Review #6)

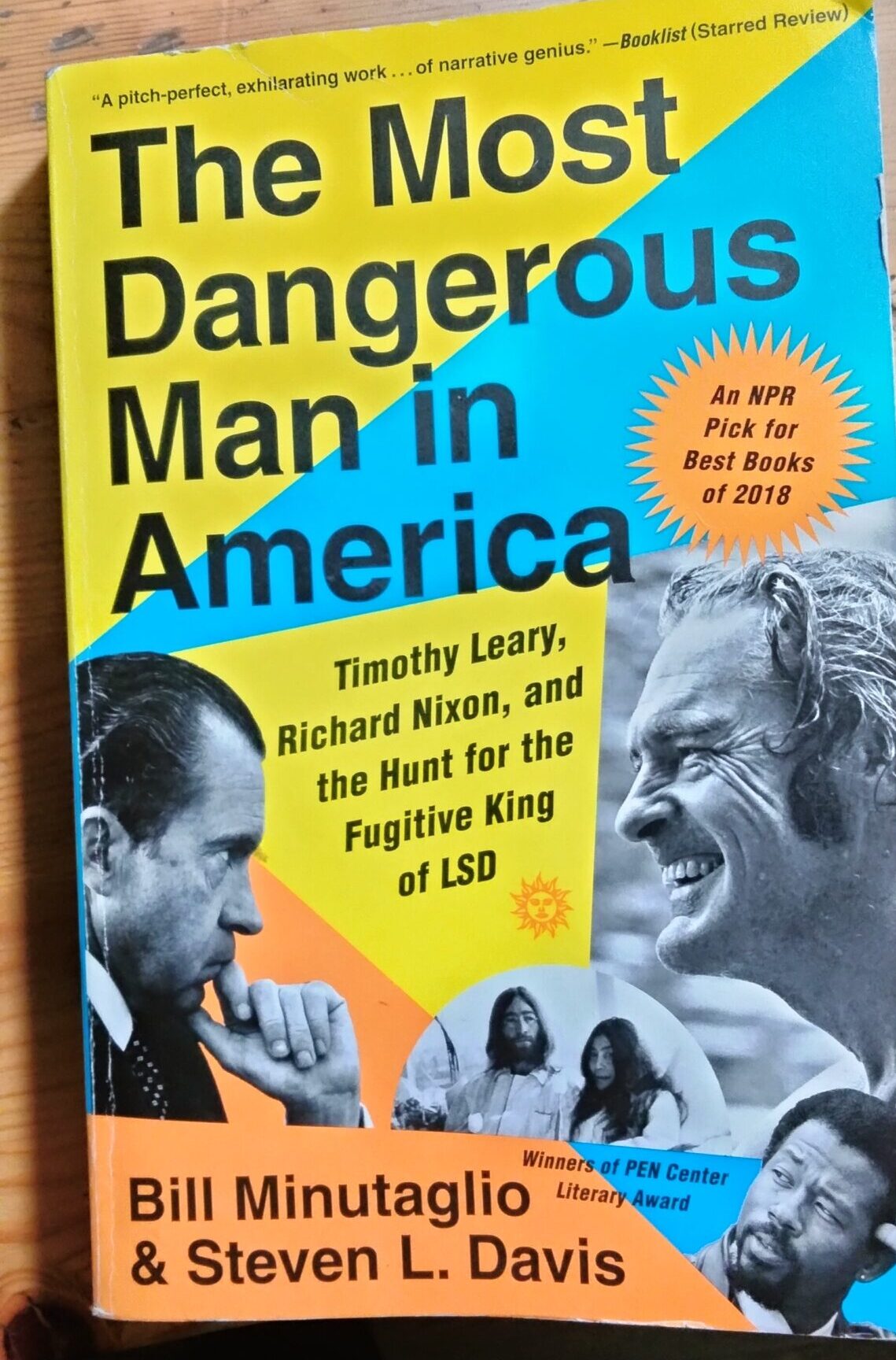

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon, and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD. By Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis. Twelve, Hachette Books. 2018. 355 pages.

Score out of 100: 83

My dad moved to San Francisco in 1966, the year before the famous Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park at which Dr. Timothy Leary urged the assembled hippies to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” Among those who lived nearby were my mom’s parents and no less than Charles Manson. Growing up, I heard a potted history of my native city in the convulsive 1960s and 1970s, so imagine my surprise at the book’s epilogue. Mr. Leary arrived in his cell at Folsom State Prison in 1973 only to chat with Mr. Manson.

“We were all your students, you know,” Mr. Manson told Mr. Leary. “You had everyone looking up to you. You could have led people anywhere you wanted. And you didn’t tell them what to do. That’s what I could never figure out. You showed everyone how to create a new head, but you never gave them a new head.”

Mr. Leary replied, “The idea is that everybody takes responsibility for his nervous system, and creates his own reality.”

Authors Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis treat the incident as another Zelig-like encounter Mr. Leary had with a legendary person in the 1960s and early 1970s; among the others were rockers John Lennon and Keith Richards, novelists Jack Kerouac and Aldous Huxley, and jazz musician Charles Mingus. Yet the book fails to treat seriously the harm Mr. Leary posed to the country and other nations. The danger was not military or political, but rather spiritual and physical. Mr. Leary was a Pied Piper for a powerful drug.

The Most Dangerous Man avoids examining the implications of Mr. Leary’s proselytizing. Instead, the book highlights his extraordinary fortitude from September 1970 to January 1973:

-

escaped from prison

-

fled to Algeria

-

lived as a guest of the Black Panthers at their plush, international embassy in Algiers

-

moved to Switzerland with his third wife

-

after she left him, he fled to Afghanistan with a woman half his age

Mr. Leary did not do these things alone. Leaders of the Weathermen, later the Weather Underground, provided him with a getaway car from prison, drove him to San Francisco and Seattle, gave him a disguise, and put him on a plane from Seattle to North Africa.

If those events sound fascinating, they were made all the more so by the authors’ blow-by-blow account. What Mr. Leary saw, heard, and felt. What he wore. Where he was. This is ticktock journalism at its most charming. I also liked the brief chapters of two or three pages, which give readers a break. And as other reviewers have noted, the authors’ use of the present tense does make the events and people seem more real somehow.

The book’s style is not in question. Its content is.

The authors acknowledge Mr. Leary was a key proselytizer for LSD; the Beatles, poet Allen Ginsberg, and fellow Harvard professor Richard Alpert were other key influencers. Yet only Mr. Leary was so effusive and as a former member of Harvard’s faculty, had the intellectual cachet.

He dubbed LSD “the most powerful aphrodisiac ever created” and said, “in a carefully prepared, loving LSD session a woman will inevitably have several hundred orgasms.” He added, “Turning on people to LSD is the precise and only way to keep war from blowing up the whole system.” Witness this 1967 interview on the PBS show “Firing Line” with William F. Buckley, Jr.

The authors acknowledge that Mr. Leary received pushback outside the Establishment for his sweeping claims. Dr. Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who discovered LSD in 1938, criticized Mr. Lee for his uncritical acceptance of the hallucinogen; LSD should be used only in the right setting and with the right people, he advised.

The authors mention that Mr. Leary’s first wife committed suicide on his thirty-fifth birthday. It stands to reason the pain of her death must have inclined him toward a dramatic pharmacological solution. The authors did not mention but could have that growing up Mr. Leary’s father left him and his mother when he was fourteen years old, although they appear to have been in contact with one another.

How much blame does Mr. Leary deserve for the harm he caused?

Some people’s lives are wrecked by using LSD, after all. They cause accidents to themselves or others, experience distressing flashbacks, and can be deadly if combined with other drugs. To be sure, LSD has been shown to help some people with mental illnesses, and the drug is not nearly as dangerous as other hallucinogens such as PCP.

Yet LSD packs a punch. It changes people’s perceptions, consciousness, and emotions. You could connect Mr. Leary’s unqualified advocacy for lysergic acid diethylamide with the country’s opioid epidemic today. In both cases, highly trained professionals lowered the barriers to obtaining a powerful drug.

Instead of grappling with or broaching the consequences of Mr. Leary’s advocacy, the authors contrast him with President Richard M. Nixon. The contrast is rich. One was an icon of the counterculture, the other the Establishment.

Yet the contrast is not as airtight as the authors insinuate. Nixon ended the Vietnam War. The number of U.S. troops in Vietnam declined to 50 in 1973 from more than half a million in 1968. Furthermore, if Mr. Nixon is your baseline of ethical behavior, you are setting the bar awfully low.

The Most Dangerous Man is a curious book. I cannot recall the last time I could not put down a book about an “amiable phony,” in the words of Mr. Buckley. He popularized a harmful drug to millions of impressionable people without warning them of its side effects. Alas, I found the book more charming than Mr. Leary but only slightly less shallow.

-30-

0 Comments