How One Nonfiction Guru Writes Faster and Better

One of the best lessons I learned about nonfiction writing was counter-intuitive. It didn’t have much to do with writerly tasks like putting pen to paper or keystrokes to the computer screen. It had to do with working like a car mechanic, an architect, a solitaire player, and a Hollywood executive.

In other words, I learned how to create an effective outline or blueprint—the most vital but least sexy and most neglected step in writing.

In the early-to-mid-2000s, I struggled to write what became my book, Why the Democrats are Blue (2007); the process took too darn long and what I wrote was mediocre at best. I needed to find a better way.

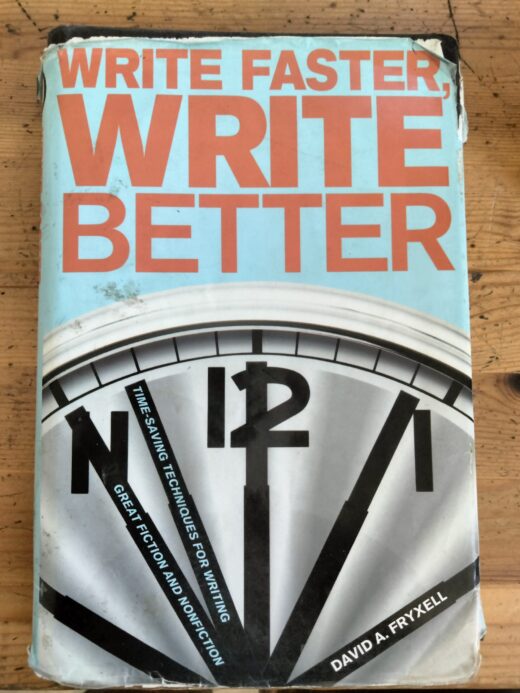

At a Barnes and Noble in Alexandria, Va., I was browsing in the section for writing. A family member spotted on a table a sky-blue hardcover book, Write Faster, Write Better (2004) by David A. Fryxell. She pointed the book out to me and suggested (or was it insisted?) I check it out. I picked up a copy and was hooked. I had found the key to the universe in the engine of an old parked car on a random table in northern Virginia.! Two to four years later, my book hit bookstore shelves. What more can a would-be author ask?!

I wasn’t alone.

In the early-to-mid 1980s, Mr. Fryxell was a columnist for the Dubuque Telegraph-Herald. To keep his job, he had to write three- and, later, four columns of 500 to 700 words each. That’s not easy! To survive, he couldn’t wing it. He needed a method, a process, a step-by-step guide.

The one he adopted worked. Not only did he keep his job, but he also became editor-in-chief of Writer’s Digest and the author of numerous books.

(Writer and author David A. Fryxell)

As Mr. Fryxell notes, better-known nonfiction writers agree that organization is the key to writing faster and better. As Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Richard Rhodes noted, “The kind of architectonic structures that you have to build that nobody ever teaches or talks about, are crucial to writing and have little to do with verbal abilities. They have to do with pattern ability and administrative abilities—generalship, if you will. Writers don’t talk about it much, unfortunately.”

What writers talk about is how to write faster or better. Probably the most common advice has to do with writing faster.

Cal Newport advises minimizing interruptions through time-block planning, retreating to a writing shed, or fixed-time productivity. Writing gurus have advised avoiding stopping and starting while you write. Others urge writers to write at the time of the day when they have the most energy, typically in the morning. The late Tom Wolfe implied writers should adopt his daily quota of drafting 2,000 words a day.

Other writers, especially those associated with the “Little Red Schoolhouse” program at the University of Chicago, argue that engaging readers produces better writing. The late U of C professor Joseph M. Williams, a personal favorite, advised establishing a shared context with readers and divulging your thesis high up.

I agree with and have incorporated those strategies. They help me write faster and better. Yet none of those strategies alone is more helpful than writing faster and better than outlining. Yes, outlining: the process you learned in elementary school.

I get it. Outlining is associated with dreariness and drudgery. With points, subpoints, and the like, who wants to do that? This resistance is unfortunate. Outlining gives order, balance, and unity to your writing. An outline is for a writer what a blueprint used to be for architects or what GPS is for a typical driver. It gives you a plan, a route, a direction.

How so?

In an interview, Mr. Fryxell said much writing online is disorganized. Ideally, writers would adopt the “inverted pyramid” style of putting the most important information up top—a perennial strategy of journalists. Instead, writers use the reverse inverted pyramid approach. “The real lead (indeed, almost any new factual info) gets buried several paragraphs deep, so readers have to scroll through multiple ad placements to reach the facts behind the tantalizing (but incomplete) headline,” he noted.

These writers lack what Mr. Fryxell calls “an inner measuring stick,” a way to create order, balance, and unity. Without one, they make irrelevant points or to readers’ dismay, steer the story down random paths. To avoid those mistakes, he advises adopting four tactics:

#1 Sketch out your main points on a legal pad or blank sheet of paper.

This step creates order in your budding story, post, or article. I do this as I would in a journal: off the top of my head, no forethought. My ideas are out of my head and onto the page. This produces a kind of “second brain” that gives me more intellectual firepower.

If I am reporting, I follow Mr. Fryxell’s approach. I read through my notebook in search of points I may want to include in the story. When I find one, I write a small number at the top left and circle it. I summarize the point on the legal pad and add the number.

I think of this step as that of a car mechanic. Before he fixes your car, he has his tools at the ready, in his shop. They’re not lost somewhere. If he is missing some, he orders or buys them.

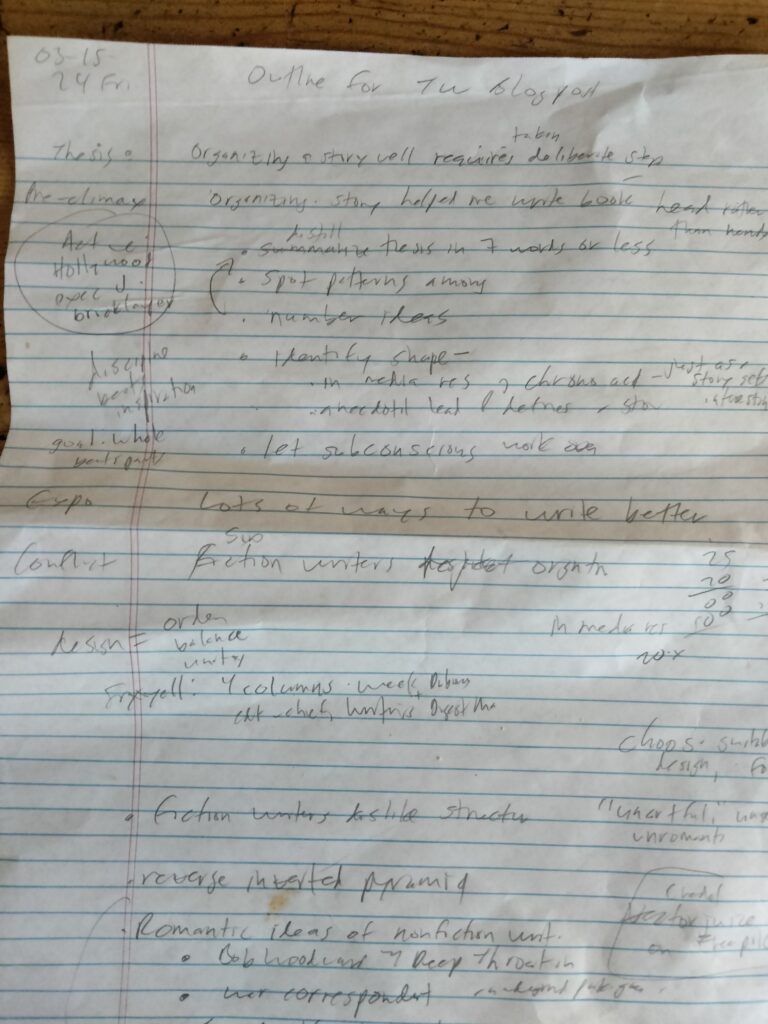

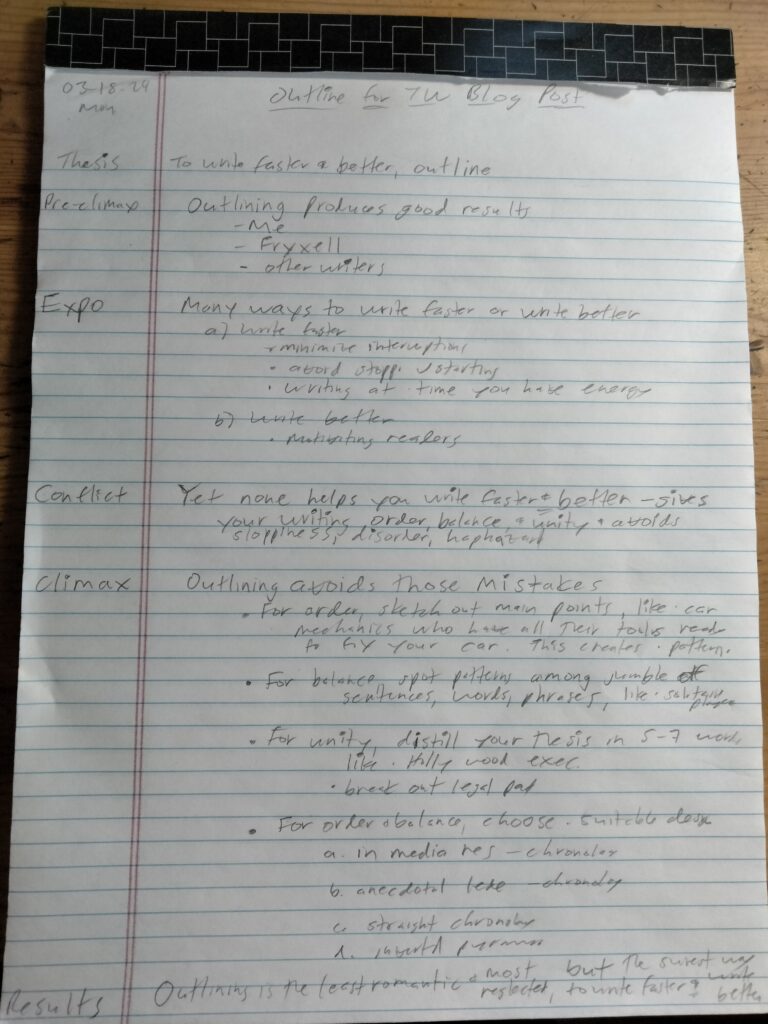

(My first outline for this post).

#2 Spot patterns among the jumble of sentences, phrases, and words.

This step creates balance in your writing. It is more daunting than the last. To spot a pattern requires concentration, and concentrating in a digital age is increasingly difficult.

Mr. Fryxell recommends letting the ideas marinate in your brain overnight and using your subconscious to spot the pattern. I vouch for this approach. The trouble is, as any journalist knows, you may not have time to let the ideas simmer. You need to devise an outline and, more importantly, crank out a story, now!

I have found success seeking to simplify my story by relating to friends and family members. For example, a story about Vladimir Putin or tech company Nvidia becomes personal. My daughter acted like Putin, then did this, then did that. Or Nvidia’s earning report did as well as my wife did in her performance review. Her bosses were over the moon. For whatever reason, breaking down the story in this way enables me to spot patterns I might not otherwise.

#3 Distill your thesis in a five-to-seven-word sentence.

This step is all about unity. You act like a Hollywood executive who combines two ideas into a simple phrase. Think “Snakes on a Plane.”

Yet as enjoyable as the step is for me, I find it can lead me astray. While “snakes on a plane” is a simple message, building a story around garden snakes on a truck bed would be more challenging.

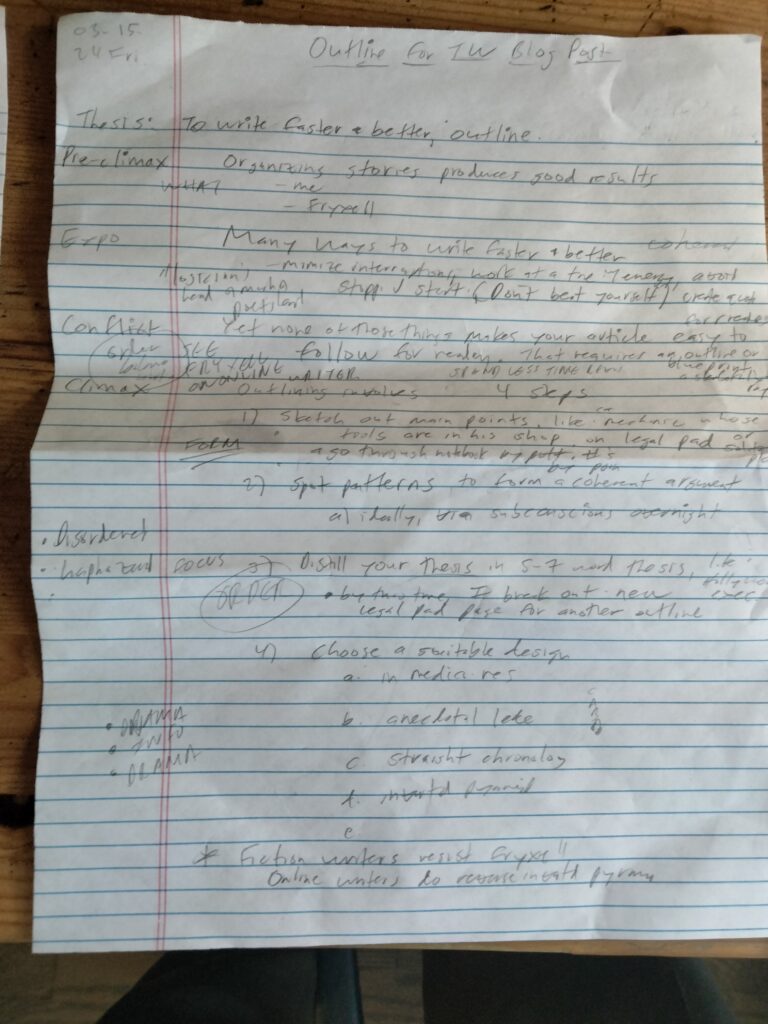

(My second outline for this post).

#4 Choose a suitable design.

The final step is finding a proper shape for the story.

In media res. This phrase is Latin for “in the middle of things.” Basically, it means the writer starts the story with a scene, anecdote, or an event as the action starts in a chronological account. An “in media res” opening imparts more drama than information to the story, a key tactic for catching readers’ attention. This may be part C in a story that proceeds chronologically from A to E. In other words, the story would be organized C-A-B-D-E.

An anecdotal lede. The intro highlights or illustrates the story’s main point. It’s a kind of synecdoche for the story itself. This is used in less chronological or narrative accounts. As Mr. Fryxell notes, The Wall Street Journal’s “middle” column adopted this lede famously.

Straight chronology. This is self-explanatory. Many memoirs and biographies proceed in this fashion.

Inverted pyramid. This is the traditional newspaper way to begin a story: cram the most important facts at the front and hope readers find them interesting enough to continue reading.

Spiral. “Some historical narratives, for example, alternate between two protagonists or antagonists,” Mr. Fryxell said. “You might have one chapter on the British preparation for the Battle of Britain, then one on the Luftwaffe, then back to the RAF, and so on.”

(The third and final draft of my outline).

How long does outlining take? I have read a dozen books about writing. None has estimated the time for each step in the process or the process altogether. I asked Mr. Fryxell, and he said 75 to 120 minutes:

If you can spend some time letting your subconscious work, the actual organizing shouldn’t take long. Marking up your notes or otherwise gathering your material might take a half-hour to an hour, depending on how much research you’ve accumulated. Coming up with the actual outline could take 15-30 minutes if you’ve given your subconscious time to work. Then connecting your notes to your outline might be another 30 minutes.

Mr. Fryxell had one word of caution, though.

A story’s word count is a poor proxy for estimating the time it will take to outline a story. A story’s complexity is a better one. I agree. A story with lots of highways and byways, ups and downs, will take more time to outline than one without them.

Outlining is a funny thing. Many writers prefer not to outline at all, and I put myself in this category. It’s tempting to skip the process altogether. Indeed, many fiction writers have admitted to Mr. Fryxell that they do skip the process. “Most pushback on my emphasis on organizing and planning has come from fiction writers,” he wrote in an email. “Some prefer to just set out without a plan, or let their characters lead them.”

You can see why. Outlining is a decidedly un-romantic, unsexy activity. As Mr. Fryxell writes in The Bones of Writing (2020) outlining will never have the cache of reporting in the field: think Bob Woodward meeting Deep Throat in an underground garage past midnight, World War II correspondents Ernie Pyle or Edward R. Murrow reporting as bombs go off in the distance, or F. Scott Fitzgerald and wife Zelda dancing at night in fountains in New York and Paris.

Yet outlining is the surest if most neglected strategy to writing faster and better. As he notes, “One writer friend, a brilliant novelist, literally had a barn full of discarded pages and drafts. I can’t argue with the ultimate results, but that does seem like a hard way to get there!”

-30-

0 Comments