How to Develop a Genius Writing Skill: Using Objects as Symbols

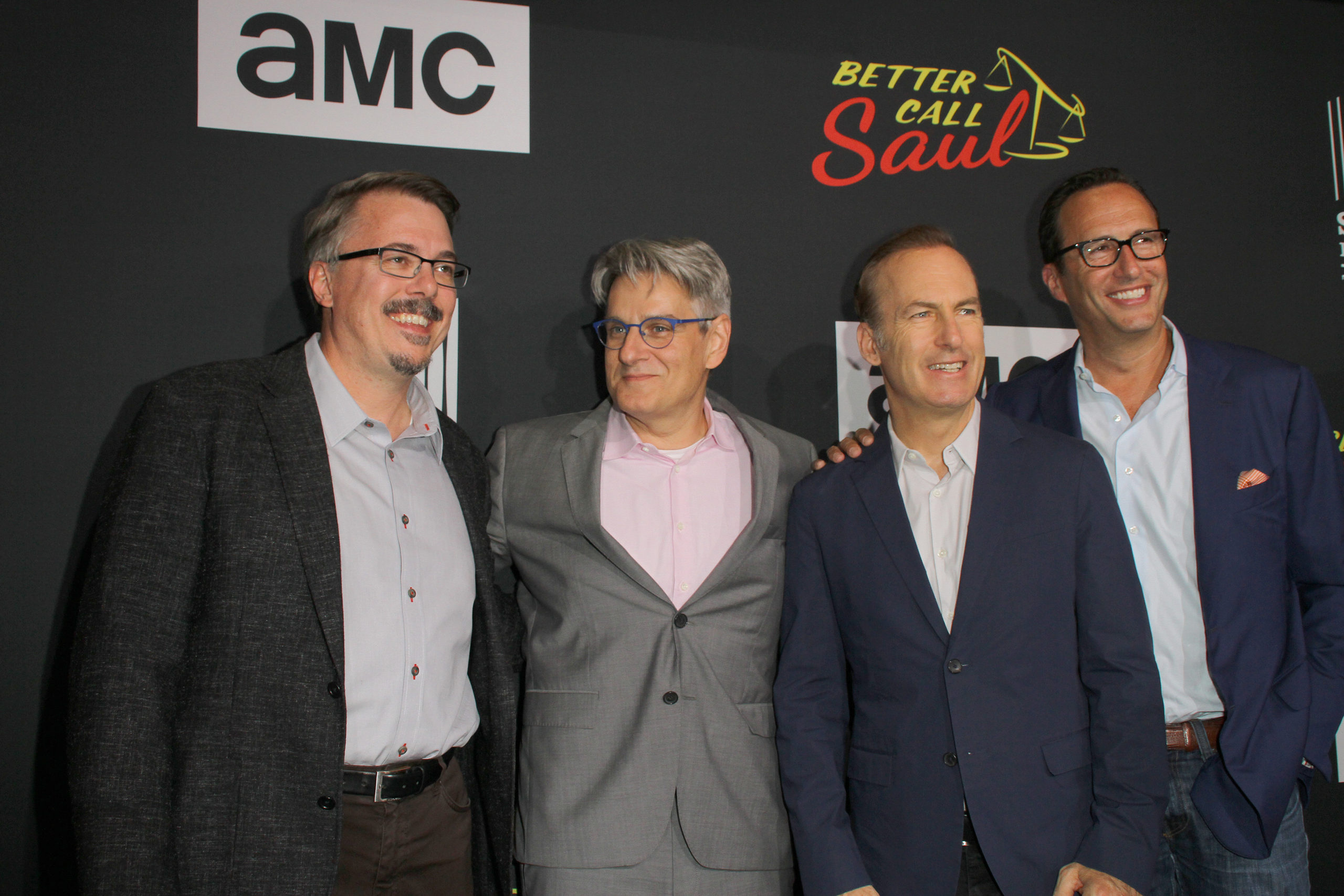

Last month, the AMC television series “Better Call Saul” began its sixth and final season. The show, a prequel to “Breaking Bad,” is one of my favorites, up there with “The Wire” and “The Sopranos.” As exceptionally written as those three shows were, “Better Call Saul” might be the best written. Among other virtues, the show uses a powerful literary technique: it presents objects as symbols. Sometimes a cigar represents nothing more than a cigar, but in “Better Call Saul” objects represent themes.

To be sure, “The Sopranos” deployed symbolic objects. In the inaugural episode, the family of ducks were a stand-in for Tony’s yearning for domestic tranquility. Yet the show did so episodically or seasonally. What sets apart “Better Call Saul” is the show uses symbolic objects throughout the series.

Take the overlarge canary yellow coffee mug with the inscription “World’s 2nd Best Lawyer,” for example. Early in the second season, lawyer Kim Wexler gives the coffee mug to her friend (or is it boyfriend?) Jimmy McGill as a wry congratulations for landing a job at the prestigious law firm Davis & Main. The mug represented their good-natured professional rivalry and accomplishments.

Alas, despite Jimmy’s best efforts he could not set the mug in the cupholder of his shining new company car. Now the mug stood for something else: the poor match between the scheming, down-to-earth Jimmy with the buttoned-up lawyers at the firm.

In season five, a bullet hole tore through the coffee mug after Mike Ehrmantraut got into a shootout with cartel figures. The bullet-laden coffee mug was a synecdoche for Jimmy’s violent clients. Yet Jimmy retrieved the mug from his otherwise destroyed car, a sign of his commitment to being an upstanding lawyer like Kim.

In the premiere of season six, before Kim and Jimmy get into a taxicab, she tosses the coffee mug in the trash. Neither retrieves it. Watching this scene, I was disappointed. As morally grubby as the duo have been, I liked their grit and empathy for the less fortunate. What did the trashing of the coffee mug mean?!

On reflection and a little online research, the answer become apparent: Jimmy is no longer a true lawyer. He’s as much a criminal lawyer as a criminal lawyer. This makes for compelling television, but it’s still sad. A con man with a good heart, as BCS expert Pete Peppers said, has turned into one representing an evil client, a cruel and murderous Mexican drug cartel.

This is what your challenge is

If I had to guess, I would say presenting objects as symbols ranks low on the list of priorities of even True Writer readers. You are far more worried, if you worry about it at all, of making your words come alive, of making them into concrete objects.

What the writer Henry Fowler called “abstractitis” is a perpetual temptation. You invoke words such as freedom, love, and wealthy and assume readers catch your proverbial drift. In fact, readers may be clueless. Words mean different things to people. To some, freedom could mean playing the video games “Fortnite” or “Halo” at home all day. To others, it means being released from the county jail.

Two ways to write physically

To “write physically” instead, I propose two strategies.

The first strategy is to write with concrete nouns in mind. As the writer and editor John Maguire wrote in The Atlantic,

An alternate approach might be to start the course with physical objects, training students to write with those in mind, and to understand that every abstract idea summarizes a set of physical facts. I do, in fact, take that approach. “If you are writing about markets, recognize that market is an abstract idea, and find a bunch of objects that relate to it,” I say. “Give me concrete nouns. Show me a wooden roadside stand with corn and green peppers on it, if you want. Show me a supermarket displaying six kinds of oranges under halogen lights. Show me a stock exchange floor where bids are shouted and answered.”

“What is a concrete noun?” a student might ask.

“It’s something you can drop on your foot,” I always answer. “It’s that simple.”

“So if I am writing about markets, productivity and wealth, I am going to….”

“Yes indeed—you are going to write about things you can drop on your foot, and people, too. Green peppers, ears of corn, windshield wipers, or a grimy mechanic changing your car’s oil. No matter how abstract your topic, how intangible, your first step is to find things you can drop on your foot.”

Mr. Maguire did not point this out, so I will: concrete nouns affect the five senses—touch, taste, smell, hear, and feel. If a noun appeals to one of the senses, use it. If it doesn’t, cut it out.

The second strategy is to report, report, report.

Words don’t appear out of the ether; they appear because you apprehend them. Take the famous car chase scene in the 1971 Oscar-winning film The French Connection, for example. Director William Friedkin and producer Philip D’Antoni “spitballed” or hatched the idea after getting out of their cars in New York, walking under subway tracks, and concluding no filmmakers had shown a scene of a car attempting to catch a subway train.

In his 1970 New Journalist manifesto, Tom Wolfe noted that losing sight of the importance of reporting is easy:

Literary people were oblivious to this side of the New Journalism, because it is one of the unconscious assumptions of modern criticism that the raw material is simply “there.” It is the “given.” The idea is: Given such and such a body of material, what has the artist done with it? The crucial part that reporting plays in all storytelling, whether in novels, films, or non-fiction, is something that is not so much ignored as simply not comprehended. The modern notion of art is an essentially religious or magical one in which the artist is viewed as a holy beast who in some way, big or small, receives flashes from the godhead, which is known as creativity. The material is merely his clay, his palette . . . Even the obvious relationship between reporting and the major novels—one has only to think of Balzac, Dickens, Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and, in fact, Joyce—is something that literary historians deal with only in a biographical sense. It took the New Journalism to bring this strange matter of reporting into the foreground.

From thinking and reporting to writing

To repeat, I urge writers should think in terms concrete nouns and to report. These two steps help you bring your mind down the ladder of abstraction. You shift from the fourth or highest level, the one with abstract words such as freedom and love, to the first or lowest level, the one with words such as “Fortnite” and green peppers.

Once you are skilled in these two steps, you can tackle the third step: using symbolic words throughout a story.

Take journalist Jimmy Breslin in his 1960s-era story for The New York Herald Tribune on the Teamster boss Anthony “Tony the Pro” Provenzano before his sentencing on charges of extortion. As Mr. Wolfe noted, Mr. Breslin got the story because he arrived on the scene before the Teamster boss appeared before the judge. This allowed Mr. Breslin to notice details he might otherwise miss. In an opening scene, he wrote the following:

“Then [Tony] spread his legs a little and went at this big guy named Jack, who had on a gray suit. Tony stuck out his left hand so he could throw a hook at this guy Jack. The big diamond ring on Tony’s pinky flashed in the light coming through the tall windows of the corridor. Then Tony shifted and hit Jack with a right hand on the shoulder.

By the story’s end, Tony the Pro is a beaten-down palooka. The judge gives him a stiff sentence. Rather than end on this note, Mr. Breslin ended it with a scene of the victorious prosecuting attorney eating in the courtroom cafeteria.

“Nothing on his hand flashed. The guy who sunk Tony Pro doesn’t even have a diamond ring on his pinky.”

The reason using symbolic objects is powerful

I don’t know about you, but the essay sticks with me. The ring pinky symbolizes criminal decadence in the first scene and its absence shows the prosecutor’s nobler career motives. According to screenwriting guru John Truby in The Anatomy of Story, using objects symbolically is to make them part of a “symbol web.” The object stands in relation to other objects, people, and actions.

I think the symbol web helps explain the symbolic objects’ curious emotional effect. The symbols make you feel invested in the story. The raft in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn suggests the precarious state of racial reconciliation and integration. The green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in The Great Gatsby symbolizes the falseness of a purely material conception of The American Dream.

Twain and Fitzgerald, like Better Call Saul’s writers, excited readers’ minds and hearts. Writers can’t expect much more than that.

What did everybody think?

-30-

0 Comments