The Art of Effective Writing, Part II: Rhetoric Adds Value

Updated: July 22, 2021

In my last post, I argued professional writers should avoid self-expression and tread carefully with the use of the first person. That was my case against literary subjectivity. Nobody cares about your childhood, breakfast this morning, or opinions of world affairs, so why write about them on Facebook and Twitter?

After all, we want to avoid the fate of Sleeping Beauty in a classic “Fractured Fairy Tales” skit. She put people to sleep not because of her allure but rather because she was a crashing bore!

I could flip this anti-subjectivity argument on its head. Readers care only what affects them. While they are indifferent to you, they care about themselves… The bastards are self-serving as us, except they pay the bills!

While some writing gurus ignore this insight, others acknowledge it. In Follow the Story, James B. Stewart, then a Wall Street Journal writer and editor, sounded sorrowful as if coming to grips with a friend’s death:

While editing the front page of the Journal, I had to confront and accept the fact that the average reader isn’t interested in much of anything outside his immediate self-interest. This is, of course, an exaggeration. Any given individual is interested in something; some people are interested in many things. But the odds that someone shares those interests with anyone else, let alone with all the two million people who subscribed to the Journal, seem quite remote.

In The Oxford Essential Guide to Writing, the late Thomas S. Kane struck a more upbeat tone:

Ask yourself questions about your readers: What can I expect them to know and not know? What do they believe and value? How do I want to affect them by what I say? What attitudes and claims will meet with their approval? What will offend them? What objections may they have to my ideas, and how can I anticipate and counter those objections?

Larry McEnerney, the former head of the writing program at my alma mater, the University of Chicago, would quibble with the last sentence. In a popular video on YouTube, he urged writers to ignore what’s inside their heads:

What is professional writing? It’s not conveying your ideas to your readers. It’s changing their ideas. Nobody cares what ideas you have.

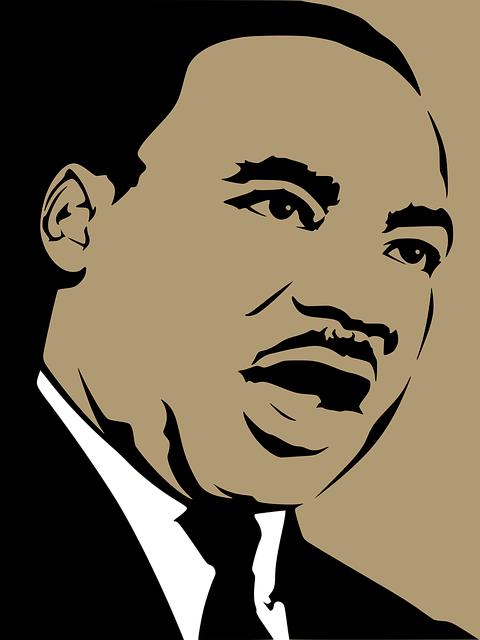

Mr. McEnerney refers to rhetoric, an Aristotelian idea which, at its best, is associated with Pericles’ funeral oration, President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address or Second Inaugural, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. While he didn’t use the term, he endorsed the concept. He urged writers to persuade an audience to embrace an idea or philosophy. “In the great majority of cases, the text advances the readers’ understanding of something they already cared about,” he said in the video.

Rhetoric should be thought of as self-expression’s better half. It addresses readers’ interests, not yours. It seeks to change readers’ minds and deeds, not yours. Imagine creating a Twitter or Facebook account in the name of your readers, and you will get the picture.

Saying we put readers first is one thing. Doing it is another. How can we?

Step #1: Use Words that Acknowledge Others

One tactic is proper word choice. In his lecture, Mr. McEnerney advised students to use words such as “widely,” “accepted” and “reported.” These show writers are addressing readers rather than themselves. As a side benefit, writers can’t be dismissed out of hand as blowhards or narcissists… (Which is a start!)

The strategy is to think like a salesperson. It’s like you’re knocking on doors and hawking vacuums or encyclopedias. The customer has a problem. We provide the solution.

Step #2: Show Readers their Knowledge is Unstable

In a handout for Ohio State students, Mr. McEnerney described his strategy. His keyword was “instability”: Writers should show readers their understanding of an issue, person, thing, or event is amiss. Or it is wrong, doesn’t fit, causes tension, or contradicts something else. Readers think their diet, financial plan, or relationships are fine. In fact, as the professional writer shows, their understanding is inadequate.

Step #3: Show Readers their Unstable Knowledge Has a Cost

Readers may see instabilities as separate from problems, however. Why should they understand in full rather than in part? This question undermines writers who seek to “add a missing piece to the puzzle,” “fill in the blank,” or “contribute to a richer understanding.”

Mr. McEnerney called this the “gap problem”: Often readers are casual about their ignorance. They’re doing fine as is. Who cares?

To address this problem, writers should emphasize costs and benefits. Their inadequate understanding has a cost: smoking a pack of cigarettes a day increases the risk of contracting lung cancer. Stabilizing their understanding has a benefit or benefits: quitting smoking increases the odds of being healthy.

Often, marshalling rigorous and elaborate studies are unnecessary. Writers can remind readers their understanding is inadequate and harmful. Few readers need to be shown drinking sugary sodas or salty snacks undermines their health. They know it already.

I wish I could proscribe rhetoric as the solution to professional writer’s problems… Take two doses of rhetoric and call me in the morning!… It’s not, though, or isn’t in popular professional writing anymore.

Rhetoric is associated with the characteristic vices of the salesman: phoniness and deceitfulness. Removing the whiff of inauthenticity from rhetoric is possible, and I will show how writers can do so in the next post.

– 30 –

I saw the video first and went looking for more, Larry McEnerney reminded me of my creative writing teacher from college. …I thought he cared, now I wonder.

Now I want to know what I should know.

I disagree. I studied Rhetoric in the graduate program at Berkeley, and spent 30 years in software marketing and sales. I believe the art of rhetoric, done well, is highly moral. You cannot be effective at persuading an audience unless you know their arguments as well or better than they do. In the course of doing so, you may well become convinced that they are right, at least about some things, and you are wrong.