The Best Book on Jonestown Came Out in 1982. That’s a Problem.

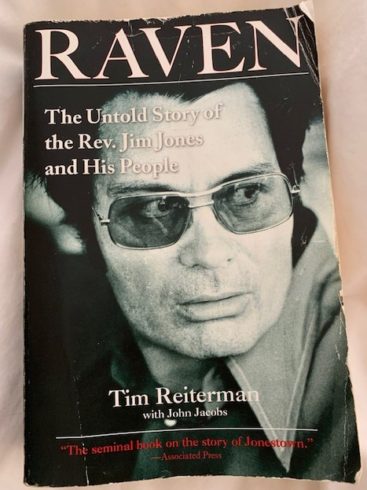

My pick for the best book on cult leader Jim Jones is one that came out early in Reagan’s first term. That would be Raven: The Rev. Jim Jones and His People by Tim Reiterman with John Jacobs.

Published a mere four years after the massacre in Jonestown, Guyana, Raven has two overwhelming virtues. The book is near-definitive about Jim Jones, or as definitive as a single volume can be.

And the author was a first-hand witness at the Port Kaituma airstrip, where five people, including Congressman Leo Ryan, were shot dead by Jones’ henchmen. (Mr. Reiterman took two bullets in his left arm).

The book’s unbeatable research about Mr. Jones explains the interest of “Breaking Bad” creator Vince Gilligan, who as recently as 2017 was among those who intended to develop the book into a limited series show for HBO.

At 626 pages, Raven has so many insights into Mr. Jones that I feel inadequate to describe the major ones. Here is my attempt to outline them:

Part One. Jim Jones’ antisocial behavior began early. As a junior in high school in Lynn, Indiana, in the mid-to-late 1940s, he shot a BB gun at his friend Don Foreman, hitting him in the stomach, and shot live rounds at him twice. The last time, Mr. Foreman was guilty of telling his friend he wished to leave his house and doing so.

Part Two. In his 20s and 30s, Jones evolved into a complex figure. He was both an atheist and a minister for the Disciples of Christ church in Indianapolis, a communist and socialist who became that city’s first paid human rights director, a local civil rights leader and a self-proclaimed god.

Parts Three and Four. After Jones moved his Peoples Temple church from Indiana to California in 1965, he was no longer satisfied leading his followers. He wanted to control them. He continued his fake healings of members at church services, staged assassination attempts on his life, and demanded sex from male and female followers alike, among other things.

His domineering behavior did not stay secret. In September 1972, San Francisco Examiner reporter Lester Kinsolving reported Jones had armed bodyguards, while his lawyer claimed the Reverend Jones raised people from the dead.

Part Five. By the fall of 1973, Reverend Jones was committed not only to controlling his followers but also to dodging responsibility for his sins and crimes. He had his church build a settlement far away from investigators: a jungle outpost in Guyana, South America. And almost certainly, he bribed a municipal court judge to destroy all records after his arrest on an indecency charge in Los Angeles in 1973.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco Jones was gaining political power. He helped elect state Senator George Moscone mayor of San Francisco in 1975. The following year, he gained enough chits that he was named director of the agency that directs the city’s public housing and was feted at a dinner whose guests included Mayor Moscone, Assemblyman Willie Brown, and Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally.

Jones’ growing stature in San Francisco was a mixed bag. He escaped accountability in some ways but not in others. After Moscone’s mayoral opponent claimed of election fraud, Mr. Moscone named Jones’ lawyer, Tim Stoen, in charge of an inquiry into the charges. The probe found no evidence of fraud.

Another probe found more. In a profile for New West magazine in the summer of 1977, Chronicle reporter Marshall Kilduff and staff writer Phil Tracy documented numerous allegations by Temple member of Jones’ physical and mental abuse. That summer, Jones moved his congregation to Guyana.

Part Six: Jones’ paranoia about eluding accountability reached new heights (or lows) in Jonestown. A paternity case in which he claimed to be the father of Tim Stoen’s son, John, set him off. Jones was asked to appear in court in Georgetown, the country’s capital. Instead of showing up, Jones led his followers into suicide drills for days.

Part Seven: Contrary to his detractors’ propaganda, Congressman Ryan was an accomplished, tenacious, independent, and compassionate man. An old acquaintance had revealed his misfortunes at the Temple’s hands in 1977, to Reiterman no less, and Ryan met with him at his home in San Bruno, in his district. Jones sought to thwart Ryan’s attempt to investigate his jungle compound to no avail.

Ryan, 53, entered Jonestown on November 17, 1978. He played nice the first day and investigated thoroughly the second and last day. Sixteen Temple members left him, while another 10 escaped through the jungle. Instead of accepting defeat, Jones ordered his followers to assassinate Congressman Ryan. This accomplished, they returned to Jonestown, where “Emperor” Jones ordered parents to murder their children. Those who refused were poisoned. In all, 918 people, including Jones, died.

All this said, Raven has competition. Other books about Jonestown are better written. Julia Scheeres’ A Thousand Lives and Charles A. Krause’s Guyana Massacre have more literary flair. In addition, Daniel J. Flynn’s Cult City and David Talbot’s Season of the Witch have more perspective and context for Jones’ dealings in San Francisco.

Yet Raven’s research about Jones is unsurpassed. Even Jeff Guinn, an accomplished non-fiction writer, paid tribute to Messrs. Reiterman and Jacobs by quoting the book for long stretches of his 2017 The Road to Jonestown.

Jim Jones is not the full story about Peoples Temple or Jonestown, of course. As Leigh Fondakowski and Margo Hall wrote in Time this week,

Time after time, we see the people of Jonestown described as “blind followers” and Jim Jones as the “cult leader” who ordered them to die. In this narrative, Jones is all-powerful, the people are robbed of personal agency, and the group becomes a blip in history, lumped in with other cults – everything from Heaven’s Gate to NXIVM. Until we open up this narrative, we not only glorify the abuser, we miss the opportunity to truly understand the meaning of Jonestown.

They have a point. No less a Hollywood actor Leonardo DiCaprio has reportedly agreed to star in a film about Jonestown. This is reminiscent of actor Powers Boothe playing the role of Jones in a 1980 TV movie, Guyana Tragedy: The Jim Jones Story, which won him an Emmy award.

As much as Jim Jones was central to the Peoples Temple and Jonestown saga, he was not the full story. Take it from me. The State Department’s lack of oversight of Jonestown is a key part of the picture. Congressman Ryan’s investigation is too, as was the enabling behavior of Jones’ top allies.

Yet these storylines have been overlooked or forgotten. This is a missed opportunity. Outside of war or natural disaster, more Americans died in Jonestown on November 18, 1978, until 9-11.

Has the country learned nothing about Jonestown other than its mass-murdering leader? German philosopher Georg Hegel said the “owl of Minerva flies at dusk,” which means people find wisdom after time has passed. In the case of Jonestown, so far the answer is no.

The public deserves books in which the monster is only one part of the story. Temple defector and escapee Deborah Blakey tried to light up the public imagination in her excellent 1998 memoir Seductive Poison. My friend Dan and I are attempting to do that very thing with our proposed book on Congressman Ryan. Other writers could do the same.

Four decades have passed and no one has equaled Raven. That’s as much a testament to the book’s greatness as it is a failure of everyone else.

– 30 –

0 Comments