The One Thing Jonestown Documentaries Never Tell You

We Americans have adopted a peculiar approach to learning about history. As recently as the 1960s, we read books—a format that encourages depth and nuance. Today, most of us learn about the past not through books, college courses, or museums but through documentary films and television— technologies that tend to be reductive and simplistic.

Don’t get me wrong. Sometimes, simple is better. Take World War II, for example. The conflagration pitted good against evil. Most people don’t need a more complicated or nuanced takeaway. That’s the gist of the story.

This week, another famous event, the Jonestown cult massacre of 1978, was presented in simple terms. Hulu aired a three-part series, “Cult Massacre: One Day in Jonestown.”

The promotional copy sounded promising: “Told by survivors and eyewitnesses, along with rare footage and rare Jim Jones recordings, the powerful series gives an immersive look into the final harrowing hours leading up to one of America’s darkest chapters.”

Unlike some Jonestown documentaries, especially the early ones, Hulu’s showed the catastrophe was as much as or more of a mass murder than a mass suicide. The 300-plus children who perished did not die willingly, and a good number of victims had puncture marks on their upper arms, a wound that suggests they were injected with cyanide-laced needles.

This insight is not to be underestimated. I once heard New Yorker writer Jeffrey Toobin, the author of a book about Patty Hearst, another infamous Bay Area resident in the 1970s, describe Jonestown as a mass suicide.

Further, the series showed Jonestown was a de facto prison. While some residents liked living in the tropical colony, others felt “trapped” and “caged.” Jonestown was a prison masquerading as a socialist utopia, but it was a prison in effect for many.

In addition, the documentary showed an underappreciated reason for Jones’ success at attracting followers. He could be tender and warm-hearted, especially toward African Americans at a time when few whites were.

In Jonestown Docs, It’s the Same As It Ever Was

Yet the main takeaway from “Cult Massacre” was no different from that of all other documentaries about Jonestown. The massacre was inevitable; Jones was an unstoppable force; nothing was to be done. Jim Jones was too powerful, too drugged up, and too evil. He was bound to kill his followers through suicide or murder.

(Peoples Temple promotional material circa 1976)

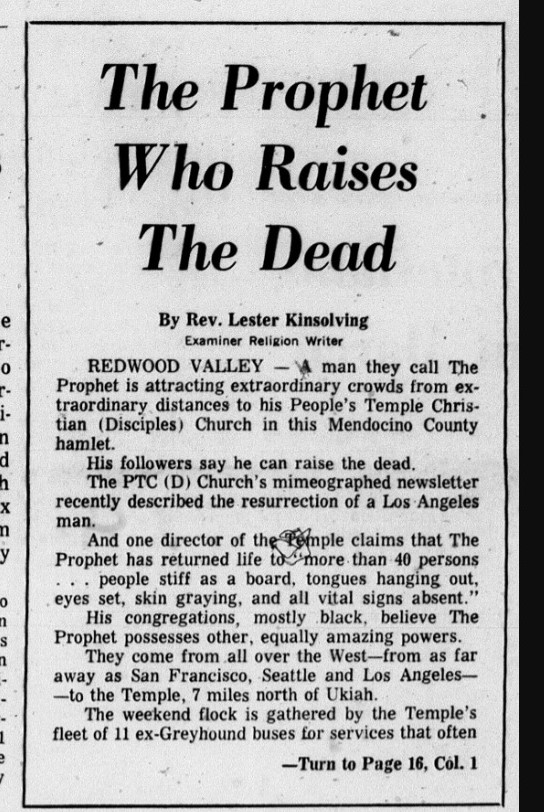

From 1971 to mid-1978, nine government agencies and one religious body—the Church of Christ, the religious denomination the Peoples Temple belonged to—inspected or investigated Jones for fraud, misdemeanors, and crimes. While conservatives and I have criticized San Francisco Democrats and city officials for failing to stop Jones, they had plenty of company.

The Indiana Board of Health and Education. Los Angeles County. The Mendocino County Sheriff’s Department. The San Francisco Special Prosecution Unit. The Treasury Department. The State Department. The government of Guyana. The FBI.

Each government agency swung at Jones and missed. He moved away; investigators messed up; or tiny things went wrong.

The Officials Who Could Have Stopped a Mass Death

For one thing, Jim Jones wasn’t a master villain as many have claimed. He made not only mistakes but bad mistakes.

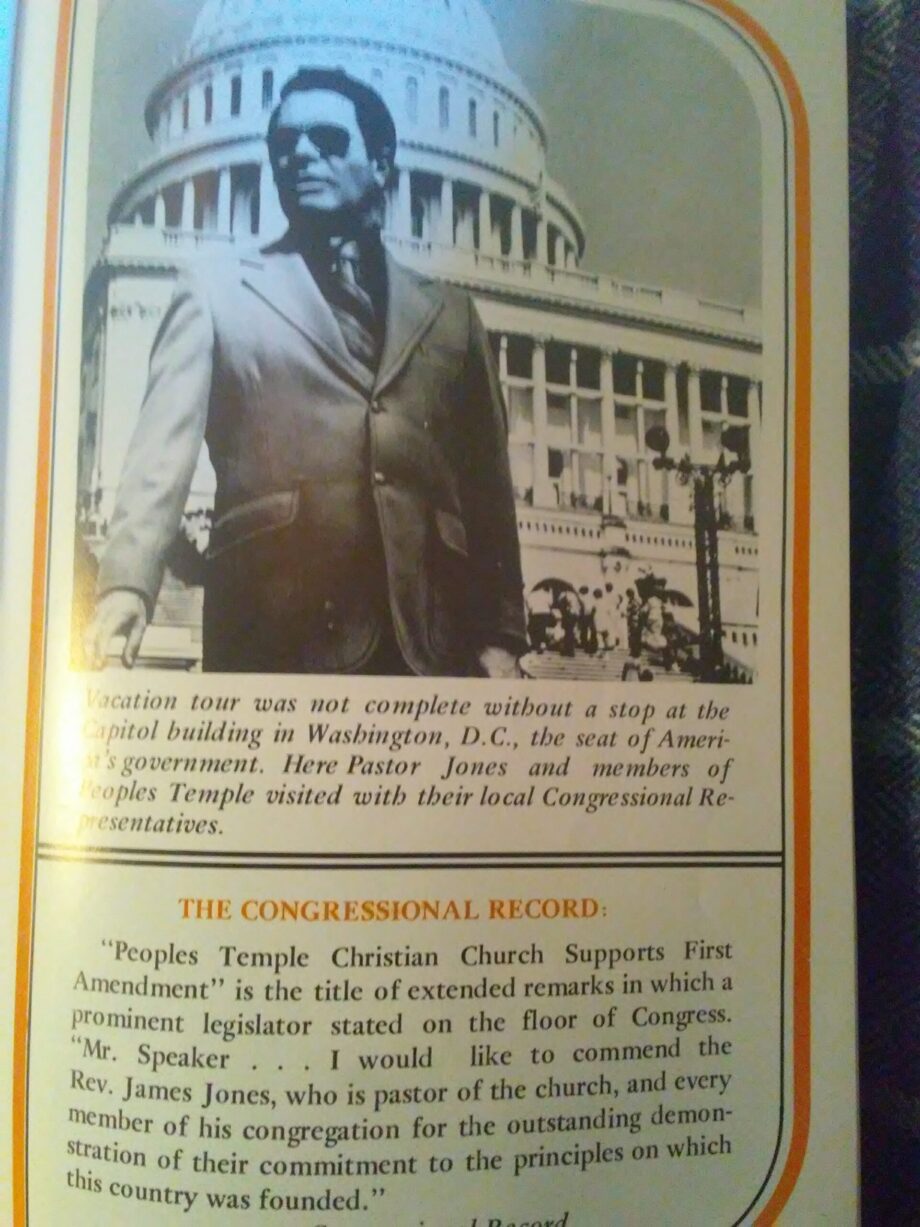

In 1972, his attorney, Tim Stoen, said Jones revived more than forty people from death. From death! Like Lazarus! As my friend Dan Kearns asked, how hard was it for government officials to examine this fraudulent charge?

(The first of a four-part series in the San Francisco Examiner by Lester Kinsolving in September 1972).

For another thing, consider the story of Deborah Blakey, a Jonestown escapee. She told her story in her best-selling 1998 memoir Seductive Poison, so this does not require specialized knowledge.

In the spring of 1978, the twenty-five-year-old whistleblower warned U.S. government officials not once but twice that Jones planned to organize the mass death of his 1,000 American followers deep in a South American jungle. Blakey had been a Temple member in Jonestown, Guyana, where the Temple had its headquarters. Bent on stopping Jones, she walked into the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, and sat down with U.S. Consul Richard McCoy in his office on May 12, 1978.

By hand, she wrote a letter that said Jones was preparing to oversee a mass suicide and if necessary, to murder resisters. Back in the States a month later, Blakey elaborated on her warning. Her affidavit showed how the State Department, the agency that oversaw Jonestown, failed to detect that Jonestown residents were falsely imprisoned.

Blakey’s warnings represent one of the great ifs in American history. Jonestown resident Odell Rhodes testified in 1979 that the State Department should have conducted a major investigation of the jungle colony after Blakey escaped; if it had, the agency might have prevented what until September 11 was the deadliest civilian toll on a single day in American history.

Instead, Foggy Bottom altered its oversight not in the slightest. The agency sent out a couple of consuls to talk with residents whose family members had inquired about them, diplomats who had not inspected a prison, let alone an open-air prison camp like Jonestown.

(Image of Deborah Layton Blakey)

The best evidence that Jones could have been stopped was the investigation of Representative Leo J. Ryan, a California Democrat. His Peninsula district was home not only to a few Temple members but also their family members, many of whom complained after their loved ones disappeared mysteriously in a South American jungle.

The Right Man at the Wrong Time

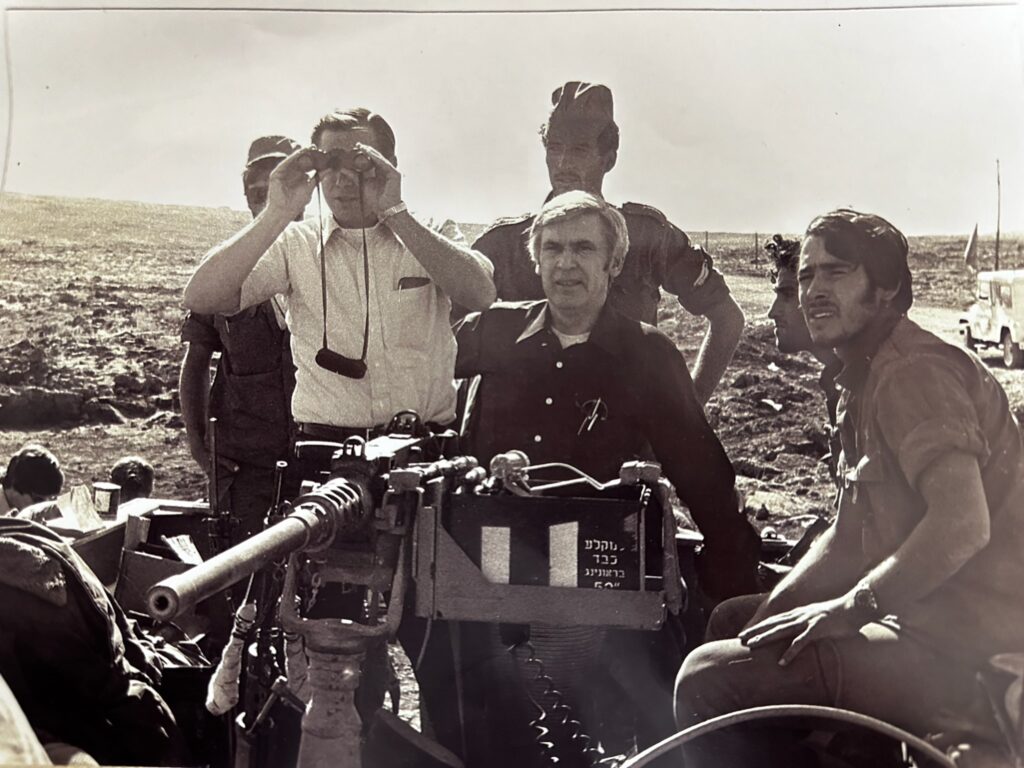

Unlike his counterparts in the government, Ryan both read about Blakey’s second warning, an affidavit, in a San Francisco Chronicle story and acted on it. This was little surprise given his background. As I mentioned in a RealClearPolitics story, before Ryan ever set foot in Jonestown, he had inspected five prisons and one jail on three continents, including East Berlin in 1970 and Tan Hiep in South Vietnam in 1974. Also, he could relate to families that had broken up unexpectedly. His father was hit and killed by a car when he was eleven years old, and his teenage nephew disappeared after joining another cult in 1976.

I will write about Ryan more in the future. For the moment, here is what you need to know.

He investigated Jonestown, held Jones to account for his crimes, liberated fifteen de facto prisoners, and saved twenty-five Americans directly and indirectly from near-certain death. You could build a strong case that if Ryan had investigated Jones all along or even in late 1977 or early 1978, he would have stopped Jones.

Instead, Ryan was a tragic hero rather than a superhero. He was among the first of more than 900 Americans who died in Guyana on November 18, 1978.

(Image of Rep. Leo Ryan in the Middle East surveying the damage after the Arab-Israeli War in the fall of 1973).

In other words, Jones should never have gotten as far as he did. He was like the abusers in the Catholic Church, universities, and Boy Scouts who for decades got away with their crimes partly because officials were clueless or incompetent. Is it asking too much of documentarians and filmmakers to set the historical record straight about Jonestown?

-30-

I think one answer might be: “if they get a new story, they’ll roll with it— IF they think it can get a more viewers.”

In battles over public memory, what sells is more key than anything else. Maybe winners don’t write the history, but the good salesmen do?

Hear, hear. 🙂