The Orwell Essay that Americans Should Read Now

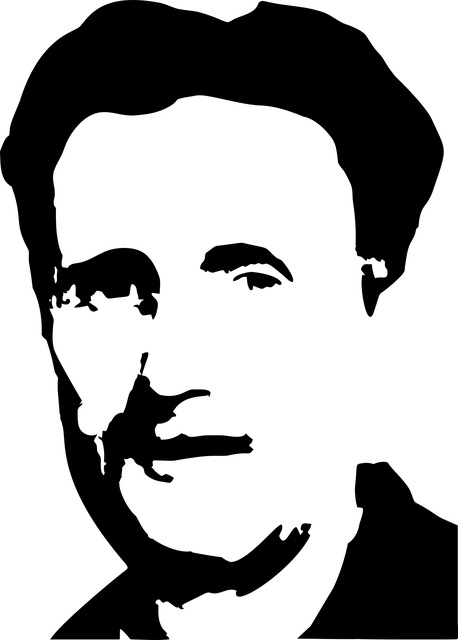

Millions of American high school graduates have read George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 or have pretended to do so at least.

The two books are widely considered classics and are even controversial to some. Who among us has not heard the saying “some animals are more equal than others” and phrases such as memory hole, the two-minutes hate, the Ministry of Truth, and Big Brother?

Of the two books, 1984 has had the greater and longer cultural cache.

Apple’s legendary 1984-style commercial for its Macintosh computer aired during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII. That was almost two generations ago. In recent years, progressives gobbled up copies of the book after Donald Trump’s election in 2016, while conservatives compared the Biden administration’s now-paused disinformation governance board to the Ministry of Truth.

Both Animal Farm and 1984 deserve their popularity. If nothing else, they are clear, dramatic, and accessible. Yet the books’ popular and critical reception has had a downside.

A near-total eclipse of the artist

The reaction to them has been almost too intense. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Bob Dylan’s albums from the 1960s, they received so much acclaim they eclipsed the artist’s other great works.

Orwell’s reputation is that of an anti-totalitarian or dystopian writer. As anyone with more than a passing familiarity with his previous seven books and many essays knows, he was more than that.

Scholars and intellectuals, to their credit, have recognized this. Some have noted in essays such as “The Art of Donald McGill” Orwell showed an appreciation for lowbrow culture. Others have emphasized his broader aestheticism such as his love of flowers and gardening.

A message you didn’t expect

What few point out is Orwell’s thoroughgoing humanism. Yes, he believed in common decency and the brotherhood of man, but above all he believed in the inestimable worth of human life. People are ends in themselves, not objects or animals to be used, Orwell insisted.

Read Orwell’s essays, book reviews, and novels today, and you are struck by the fact that the same cast of characters appears over and over. They aren’t British aristocrats, industrialists, or financiers. They are marginal and vulnerable people.

In “A Hanging” (1931), a convicted man goes to the gallows.

In Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), the poor, lower class, and hoboes eke out emotional and physical survival.

In Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), an unborn child is at risk of being aborted.

In The Road to Wigan Pier (1936), coal miners in northern England descend underground every workday.

Of Orwell’s nine books and many essays, my candidate for the most relevant expression of Orwell’s humanistic outlook for America today is “Shooting an Elephant” (1936).

Which may sound strange because the victim is an animal, but the elephant is described in human terms. The narrator compares the beast’s preoccupied style of eating to that of “grandmother,” for example.

What’s more, the story is fictional. (Orwell biographer Bernard Crick, for example, found no evidence Orwell killed an elephant). The elephant represents the colonized, or its most noble members at least, in their struggle against the colonizers.

Orwell was hardly a stranger to colonialism. From 1922 to 1927, he was an imperial police officer in Burma, a British colony now known as Myanmar. His job was not only to protect the British imperialists but also to keep order. In other words, Orwell could protect or attack human dignity.

Two problems with violence

While nowhere in the story’s 3,300 words do the words “human dignity” appear, they capture its spirit. The story shows the consequences of ripping at the fabric of life.

One consequence is stupidity.

Writers have portrayed killers as intelligent since the 19th century at least. Orwell didn’t say all killers were dumb. He said the act of killing is spiritually stultifying.

In “A Hanging,” Orwell uses the word “mindless” to describe the imperial police who execute the prisoner. In “Shooting an Elephant,” he tells a more complicated tale.

The narrator acknowledges that while the elephant did cause one man’s death, he does not need to kill the beast. (Spoiler alert). He shoots the elephant because a large crowd of onlookers expects him to do so. After all, he’s an imperial police officer:

The people expected it of me and I had got to do it; I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward, irresistibly. And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man’s dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd – seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind.

The narrator is not a heartless killer; he’s “an absurd puppet” caught up in a despotic system, imperialism, that increases the odds he will resort to killing. “When the white man turns tyrant, it is own freedom he destroys,” Orwell wrote. The narrator acts dependently. Other people control him.

A second consequence of attacking human dignity is a failure to appreciate our common dependence and vulnerability. Humans aren’t God or supermen; our powers and faculties are limited.

In Keep the Aspidistra Flying, narrator George Comstock, a down-on-his-luck poet, impregnates his girlfriend. After learning she is considering abortion, he reads a book on embryology at a library, where he recognizes that “here was the poor ugly thing, no bigger than a gooseberry, that he had created by his heedless act. Its future—its continued existence perhaps—depended on him.”

In “Shooting an Elephant,” Orwell describes the death of the elephant in painfully vivid terms:

He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken, immensely old, as though the frightful impact of the bullet had paralysed him without knocking him down. At last, after what seemed a long time – it might have been five seconds, I dare say – he sagged flabbily to his knees. His mouth slobbered. An enormous senility seemed to have settled upon him. One could have imagined him thousands of years old. I fired again into the same spot. At the second shot he did not collapse but climbed with desperate slowness to his feet and stood weakly upright, with legs sagging and head drooping. I fired a third time. That was the shot that did for him. You could see the agony of it jolt his whole body and knock the last remnant of strength from his legs. But in falling he seemed for a moment to rise, for as his hind legs collapsed beneath him he seemed to tower upward like a huge rock toppling, his trunk reaching skyward like a tree. He trumpeted, for the first and only time. And then down he came, his belly towards me, with a crash that seemed to shake the ground even where I lay.

To be sure, in the essays and novel cited above the narrator inflicts the worst possible attack on human dignity: killing. Yet Orwell noted that less egregious violence, too, was stupid. In his 1945 essay “Revenge is Sour,” he wrote that the Jewish man who kicks a German soldier after the Allies occupied southern Germany was engaging in a “childish daydream” of setting things aright.

Two ways in which an old story is relevant today

Conservatives today may object to Orwell on the grounds he was a self-proclaimed socialist.

In reality, he wrote a famous if brief critique of socialists in The Road to Wigan Pier and was denounced by a prominent British socialist, Victor Gollancz, in the foreword to the book no less, for his heterodoxy.

Orwell’s dissent was par for the course.

Each of his books expresses cultural and political disillusionment and the “smelly little orthodoxies” of ideology: imperialism (Burmese Days), pre-welfare state capitalism (Down and Out in Paris and London), religion or the Church of England (A Clergyman’s Daughter), and the artistic life (Keep the Aspidistra Flying).

Granted, Orwell was no anarchist. He praised the Edwardian England of his youth in Coming Up for Air (1939) and the solidarity among independent socialist soldiers in Homage to Catalonia (1937). Yet neither book has quite the emotional wallop of the costs of dehumanization as “Shooting an Elephant.”

While well known, the essay has yet to reach the level of canonical status it deserves. It’s a shame. “Shooting an Elephant” shows the perils of dehumanization at the hands of ideology and political systems other than Soviet Communism.

For one thing, the story is an antidote to the needless polarization in America today. Our ideological opposites may be opponents, but few are enemies. They are human beings with frailties and problems just like us.

For another thing, “Shooting an Elephant,” like Orwell’s works more broadly, lay bare the attacks on human dignity both conservativism and progressivism endorse. I won’t detail those here. Instead, I recommend reading “Shooting an Elephant” and considering in which ways your preferred ideology, hard as it is to admit, encourages attacks on human dignity.

What does everybody else think?

-30-

Great piece!