An Unjustly Neglected Book About the Jonestown Cult Massacre (Review #1)

Book Review #1: An Unjustly Neglected Book About the Jonestown Cult Massacre

(Updated: Dec. 15, 2022)

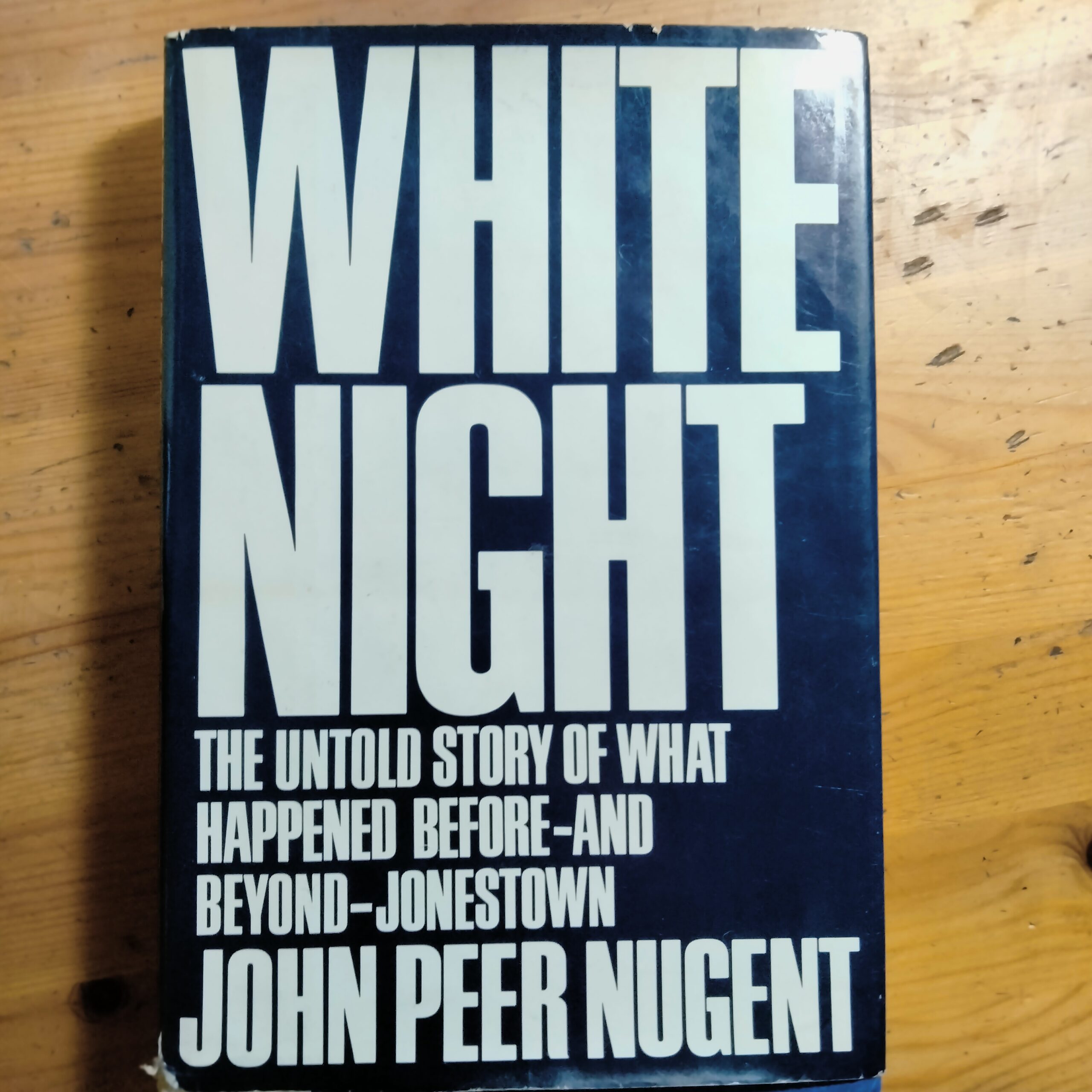

White Night: The Untold Story of What Happened Before–And Beyond–Jonestown. By John Peer Nugent. Rawson, Wade Publishers. 1979. 282 pages.

Score Out of 100: 78

As one of America’s greatest mass murderers, Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones has attracted the lion’s share of attention from historians and writers about the Jonestown cult massacre of 1978.

In Raven (1982), journalist Tim Reiterman, working with the help of fellow reporter John Jacobs, wrote a cradle-to-grave account of Jones’ life and described his lieutenants and followers.

In Seductive Poison (1998), former Temple member Deborah Layton provided a blow-by-blow account of her years as a Temple follower, including her dramatic escape from Jonestown in the spring of 1978 and attempts to warn the State Department about Jones plans for mass-suicide and -murder.

In A Thousand Lives (2011), journalist Julia Scheeres explored the lives of Jones’ followers, most of whom became victims.

In The Road to Jonestown (2017), journalist Jeff Guinn provided what was essentially an updated account of Raven, while in Cult City (2018) writer Daniel J. Flynn criticized San Francisco Democratic officials for enabling the Peoples Temple leader.

Who’ll Stop Jim Jones?

Former Newsweek journalist John Peer Nugent could have pursued a similar line of inquiry. Instead, in White Night he pursued a different one: Why the hell didn’t the federal government stop Jim Jones?

Mr. Peer Nugent’s answer has nothing to do with the CIA’s MK-Ultra program or Deep State machinations. He blames the State Department, the federal agency responsible for overseeing Jonestown, the expatriate community of 1,000 Americans in Guyana, South America.

As Mr. Peer Nugent notes, Ashley Hewitt, the head of State’s Caribbean desk, grasped the similarities between Jones and German leader Adolph Hitler only after the deaths of 918 people on November 18, 1978:

He saw the blind dedication, the racism, the thought control, the growing madness in the end—even the use of cyanide by some in the Fuhrer’s bunker under the Chancellery Gardens in 1945. He saw it then, but too late. If he had only seen it all several months before. That is not meant as an indictment of the man; it is, however, of the State Department for not reading smoke better than it does fire.

Why the State Department failed to read the smoke signals is complicated. In retrospect, State should have kept both eyes on Rev. Jones’ abuse and mass-death threats. In truth, the agency kept only one eye on him, and sometimes both eyes were shut.

Why Didn’t the State Department Stop Jim Jones?

Without going into detail, I will cite the three distractions Mr. Peer Nugent identified:

-

For the first six to nine months after the Temple’s mass emigration to Guyana in mid-summer 1977, State officials were distracted by a custody dispute between the Rev. Jones and former Temple members Tim and Grace Stoen. The Temple leader claimed to be the father of the couple’s young son, John Victor, and State officials had to weigh competing demands from U.S. and Guyanese courts.

-

In mid-1978, State officials were distracted by Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza when they should have concentrated on U.S. Ambassador John Burke’s request for greater oversight of Jonestown after Blakey’s defection and Cassandra-like warnings about impending mass death.

-

Top Guyanese officials, up to and including President Forbes Burnham, were distracted by their anger at Washington for numerous foreign-policy slights in the 1970s.

Readers of this blog know I am working on a book about Congressman Leo Ryan’s investigation of the Peoples Temple, so I think you can trust my judgment. With confidence, I can say Mr. Peer Nugent’s thesis has the ring of truth.

The State Department was more responsible for the deaths of 900-plus Americans than the other state and local agencies with jurisdiction over Mr. Jones. He operated for 15 months full time, from mid-summer 1977 to November 1978, in the State’s backyard, and State officials failed to stop him.

Indeed, the case against State’s oversight is worse than Mr. Peer Nugent indicates.

He does not mention people other than the Concerned Relatives organization contacted State about their family members in Jonestown (and attracted Mr. Jones’ ire). The family members of 47 Jonestown residents, a collection of individuals that my CQ Magazine story revealed, did too. State and Embassy officials wrote and talked with those people and yet they deferred to Rev. Jones rather than challenging him.

I give a pass to Mr. Peer Nugent for this omission, as it would have been all but unavailable to him at the time he wrote White Night, in late 1978 and early 1979. I am more critical of his failure to mention State officials bungled the handling of an August 1977 Customs bureau report that included credible accusations of gun smuggling and ex-Temple members fearing physical harm, accusations that may have buttressed the case against Mr. Jones in the eyes of Ambassador Burke and Consul Richard McCoy.

Mr. Peer Nugent was right to credit Congressman Ryan for reading Jonestown’s smoke signals correctly and unlike so many Jonestown writers, he concluded Mr. Jones would have sought to orchestrate his follower’s deaths even if the California Democrat had not set foot in the jungle commune.

Is the Book Worth Reading?

White Night is flawed. It contains numerous inaccuracies—e.g. Mr. Jones was 47 when he died, not 49 as the book asserts. And it overlooks the parental neglect Jones suffered as a child. Yet the book is worth reading to those with more than a passing interest in Jonestown.

White Night shows the difficulty of securing justice for vulnerable people. Distractions get in the way. Unless you have the training, virtues, and intense motivations of Congressman Ryan, you may wind up like Mr. Hewitt, wondering what might have been.

-30-

0 Comments