So You Want to Write a Book. Tip #1: Go to Where Your Characters Lived.

More than four in five Americans say they want to write a book. Few write one, though. What’s stopping them?

In the absence of scholarly data, I say the reason is simple: they don’t know how. Authors work hundreds and thousands of hours. Who wants to grind on a failed project?

With this question in mind, I inaugurate the first in an occasional series. (If you like this idea, please say so in the comments section below; comments help me figure out what you want to read).

This tip applies equally to writers of non-fiction, fiction, and memoirs. As I mentioned in an earlier post, places evoke emotion. Going to where you or your characters lived provides a depth of feeling for your readers difficult to achieve otherwise.

Without emotion, writing can become dry rather than vivid and evocative. Which is fine for a law review article. It’s not if you want to get a book deal with a major publisher!

Pull a Robert Caro

In Working, a collection of essays, well-known biographer Robert A. Caro described the importance of a “sense of place.” Memoir writers, too, can adopt the technique, and fiction writers like Stephen King and Richard Price have done so. In any case, Mr. Caro elaborated:

Biography should not just be a collection of facts…Once you have gotten as many of them as possible, it’s also of importance to enable the reader to see in his mind the places in which the book’s facts are located. If a reader can visualize them for himself, then he may be able to understand things without the writer having to explain them; seeing something for yourself always makes you understand it better.

… Since places evoke emotions in people, places inevitably evoked emotions in the biographer’s subject, his protagonist. Therefore, if a biographer describes accurately enough the setting in which an action took place, and if he has accurately enough presented the protagonist’s character, the reader will be helped to understand the emotions the setting evoked in the protagonist and will better understand the significance that the action held for him.

Last month, I used this technique while on a trip to greater Boston. My wife attended a medical conference there, and I tagged along partly because the late Congressman Leo Ryan, a California Democrat, spent his formative early years in the region. To the extent I could, I wanted to see and inhabit the places that helped define his life.

Why trace the steps of Leo Ryan?

For a lot of reasons, one of which is he has gotten a raw deal from journalists and historians. Some suggested or said he was naïve and out of his depth while investigating Jonestown, a de facto prison. If this was so, how do they explain Congressman Ryan had investigated five prisons on three continents already?

Others suggested or said he was a glory hound. To be sure, he was a member of Congress, few of whom oppose good publicity. Yet how do journalists and historians explain that perhaps alone among government officials Ryan could empathize with constituents whose families had broken up unexpectedly after their loved ones departed for Jonestown and were rarely heard from again?

His father died tragically when he was eleven years old; his secretary in the California State Assembly was murdered when he was forty-two; and his teenage nephew disappeared after joining a cult.

No, Congressman Ryan was the perfect investigator for Jonestown. Indeed, I consider his investigation one of the greatest and most misunderstood political deeds in American history. Ryan was skilled, compassionate, and powerful, a kind of Bobby Kennedy for ordinary people.

A Congressman’s difficult early years

While he wasn’t always heroic, he was in the summer and fall of 1978. As readers may know, Congressman Ryan was assassinated at a remote airport strip after helping liberate twenty-five Americans from Jonestown in Guyana, South America.

His death was a grim affair, and so were many of his years in North Andover. I went to the house where Mr. Ryan lived from 1934 to sometime in the 1940s, his formative years. Graciously, the owners gave me a tour and allowed me to take pictures. Here is a picture from the front porch.

This is an old country house, from the 19th and possibly the 18th century. It sat on a property of 100 acres which included a barn.

In February 1937, the funeral for Leo Ryan Sr. was held at St. Michaels’ Church in North Andover. It was held in the old church, which is used for administrative purposes according to church staff.

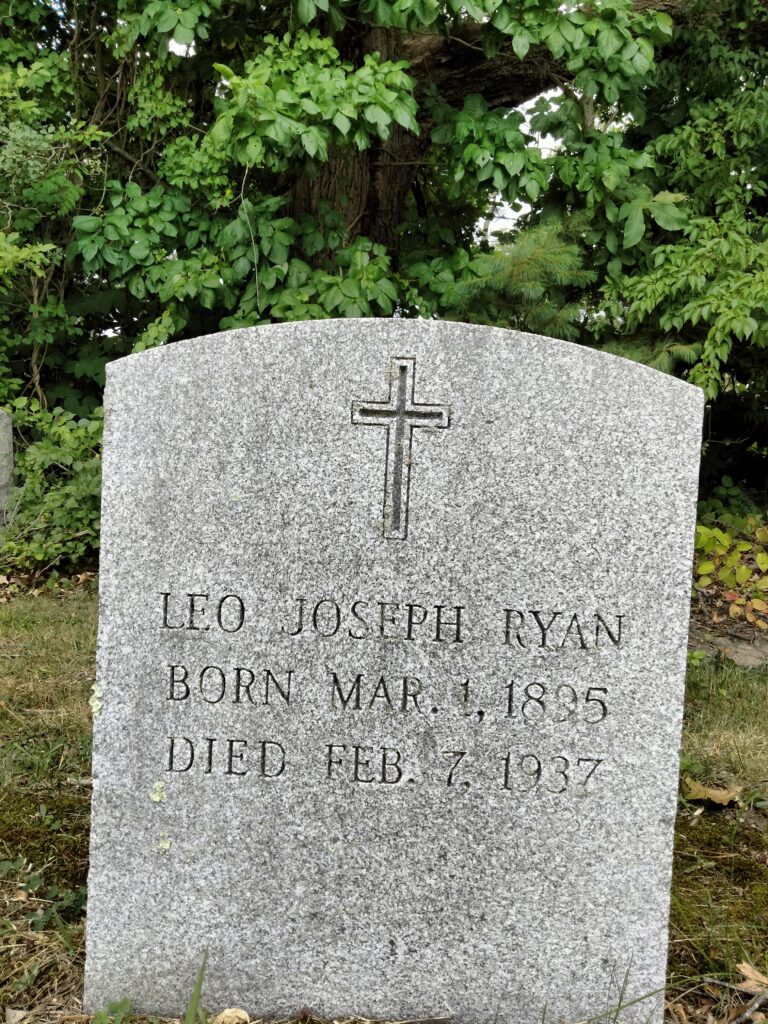

The next two images are the gravestones for Ryan’s father, as you can see, and his wife and two of their daughters. (Congressman Ryan is buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California, in his district). They are at the bottom of a hill against a copse of trees at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in North Andover, Massachusetts.

The best-known institution in North Andover is Phillips Academy in nearby Andover. Founded in 1788, the high school was and is the elite of elite prep schools. As a friend told me, think “Dead Poets Society.” President Washington greeted students and townspeople on horseback there, and among the school’s former students are George H. Bush and George W. Bush, former New England Patriots Head Coach Bill Belichick, architect Frederick Law Olmstead, and actor Humphrey Bogart, although he was expelled.

Leo Ryan went to Andover as a seventeen-year-old in the summer of 1942 on a scholarship of $40. He took a math class and failed. In any case, I am pretty sure based on the teacher he had he took the class at this building, on the edge of campus.

The other image is of yours truly on my bike in the school’s courtyard.